Bronx River Playground Pool

Location:

Type:

Size:

Year built:

Bronx

mini pool

40' x 20' x 3'

1966-69

mini pool

40' x 20' x 3'

1966-69

Claremont Pool

Location:

Type:

Size:

Year built:

Bronx

vest-pocket pool

75' x 60' x 3.5' (intermediate)

24' x 24' x 1' (wading)

1970-72

Crotona Pool

Location:

Type:

Size:

Year built:

Architect:

Bronx

WPA pool

330' x 120' x 4' (olympic pool)

1936

Aymar Embury II

Floating Pool

Location:

Type:

Size:

Year built:

Bronx

floating

82' x 52' x 4'

2006

Haffen Pool

Location:

Type:

Size:

Year built:

Bronx

vest-pocket pool

75' x 60' x 3.5' (intermediate)

24' x 24 x 1' (wading)

1970-72

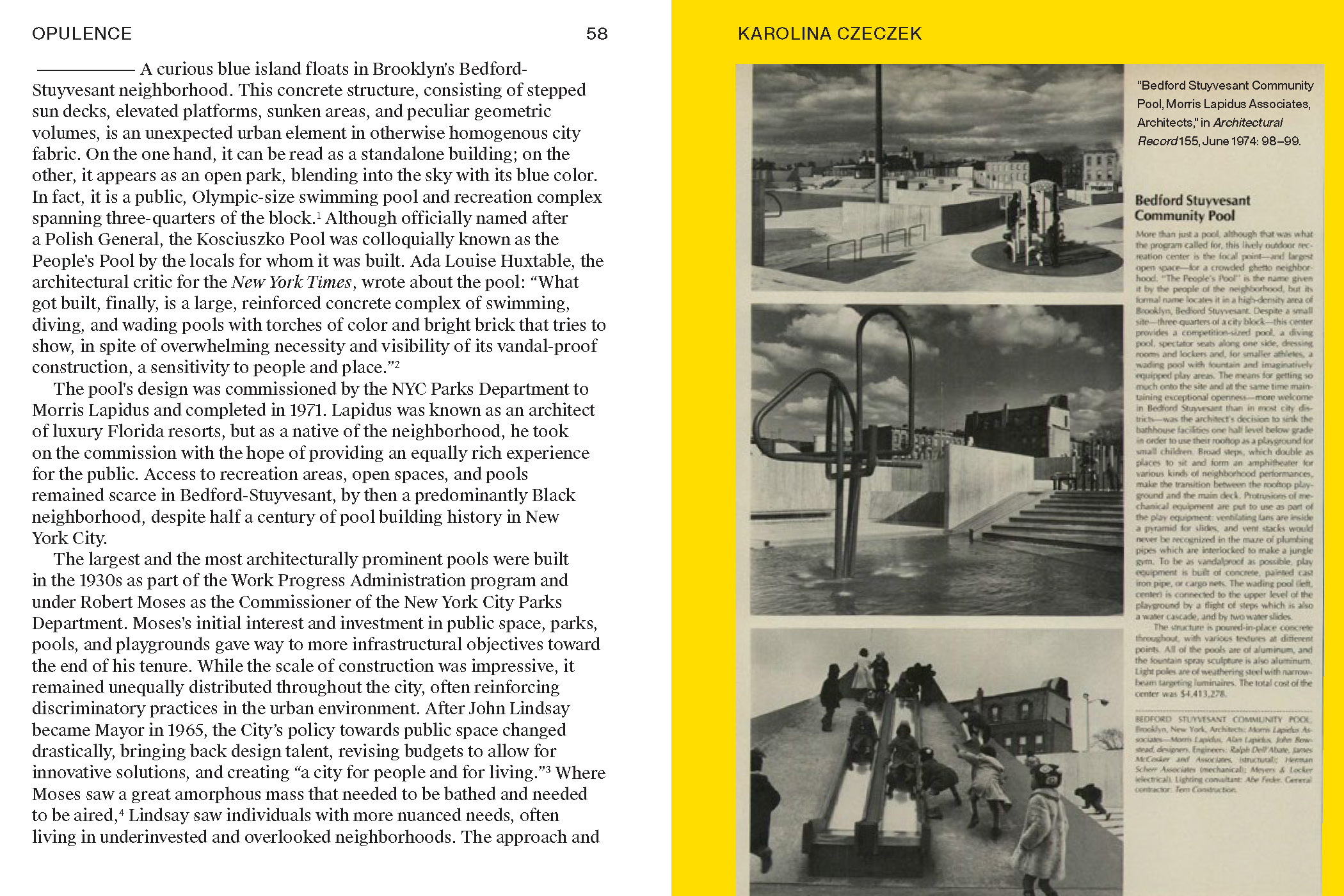

Astoria Pool, Queens, WPA pool. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

Most public pools in New York City operate only for a short period during the summer, leaving their potential largely untapped for the rest of the year. Aside from the need to build more aquatic facilities, there is an opportunity to extend the swimming season and adapt existing pool grounds for alternative uses during the off-season. Pools can be reimagined as sites for social gathering, education, and health-related programming, expanding their role in the urban fabric beyond traditional recreation. To make this long-overdue transformation possible, the research advocates for an integrated approach that brings together architectural design, programmatic innovation, and supportive policy frameworks.

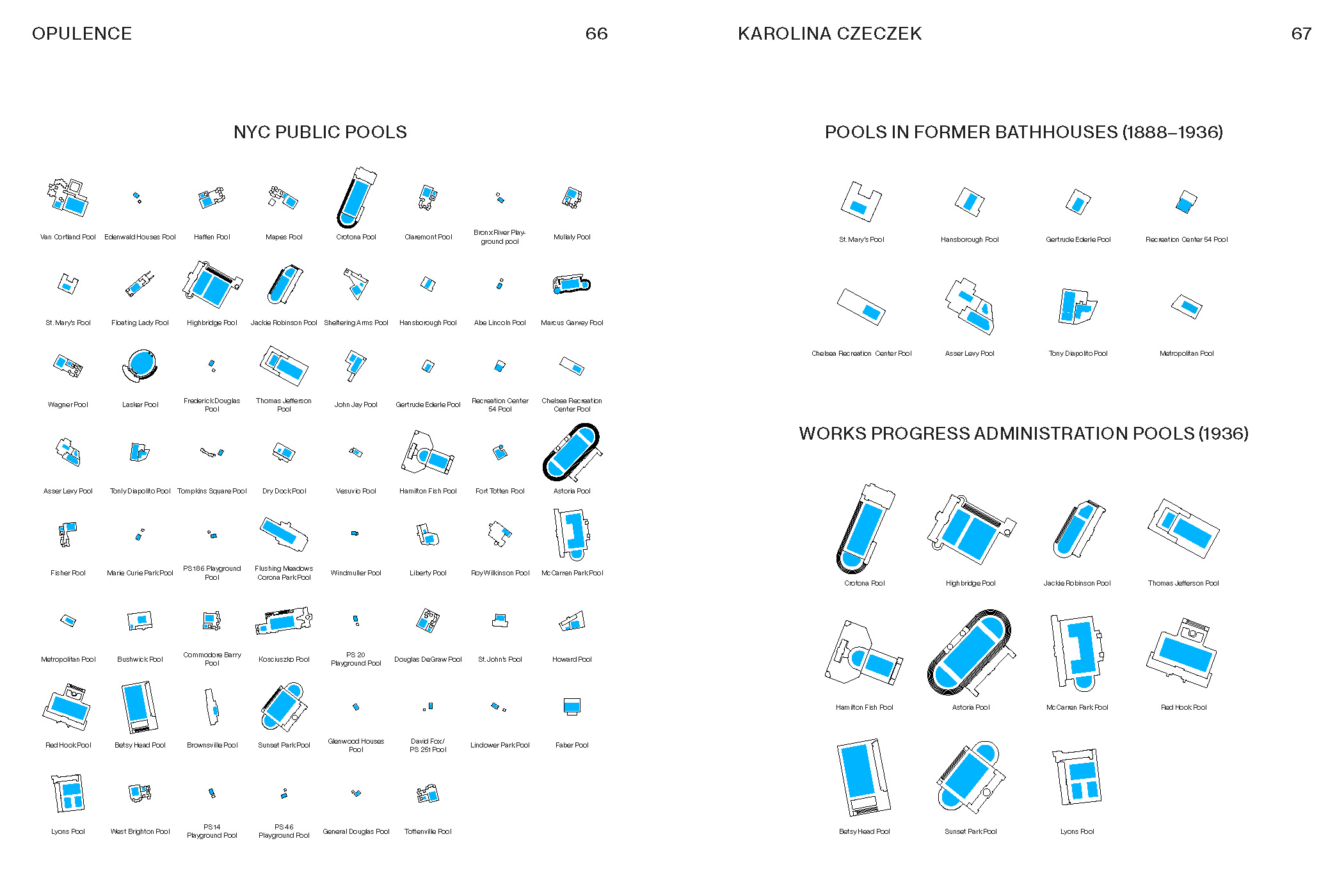

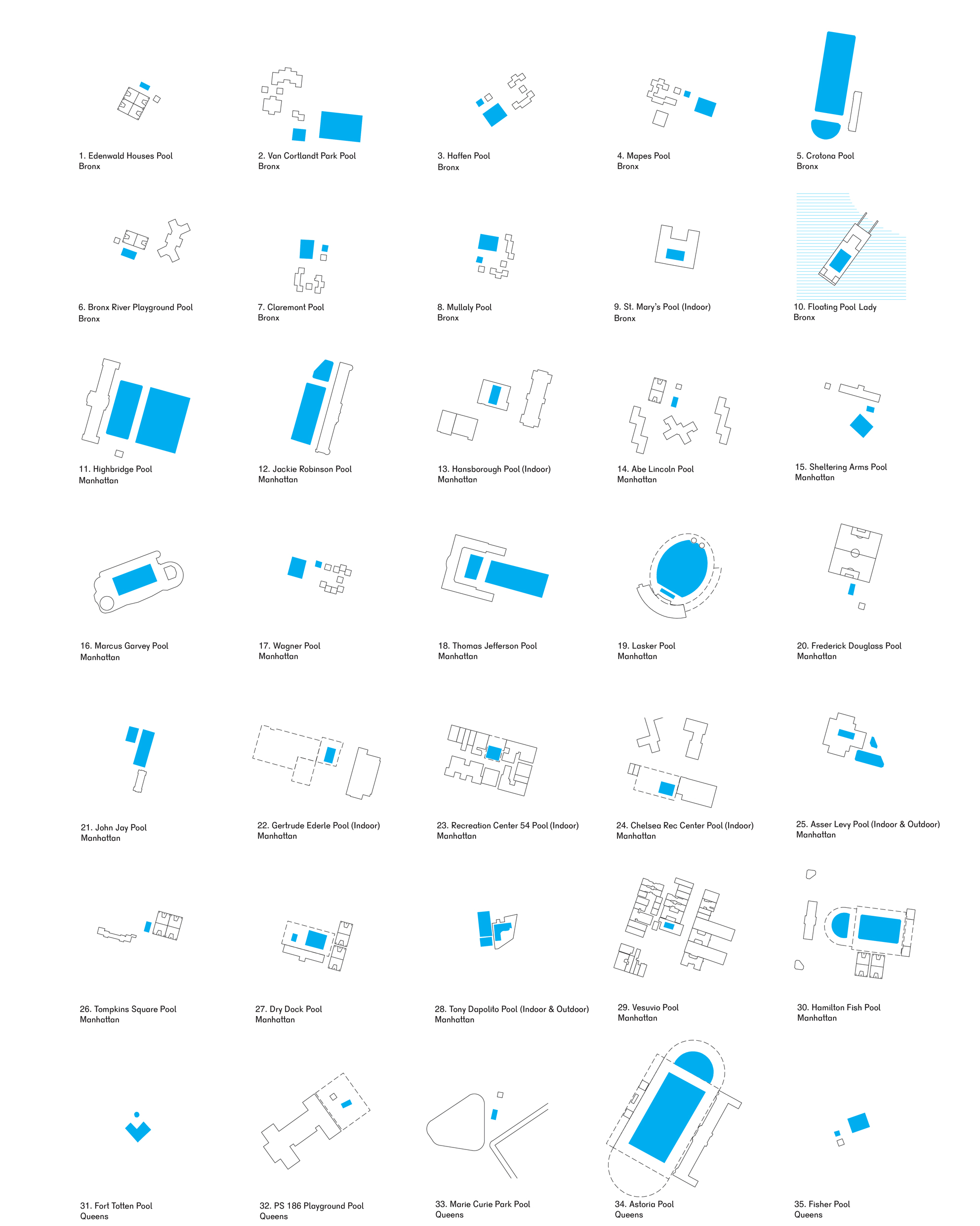

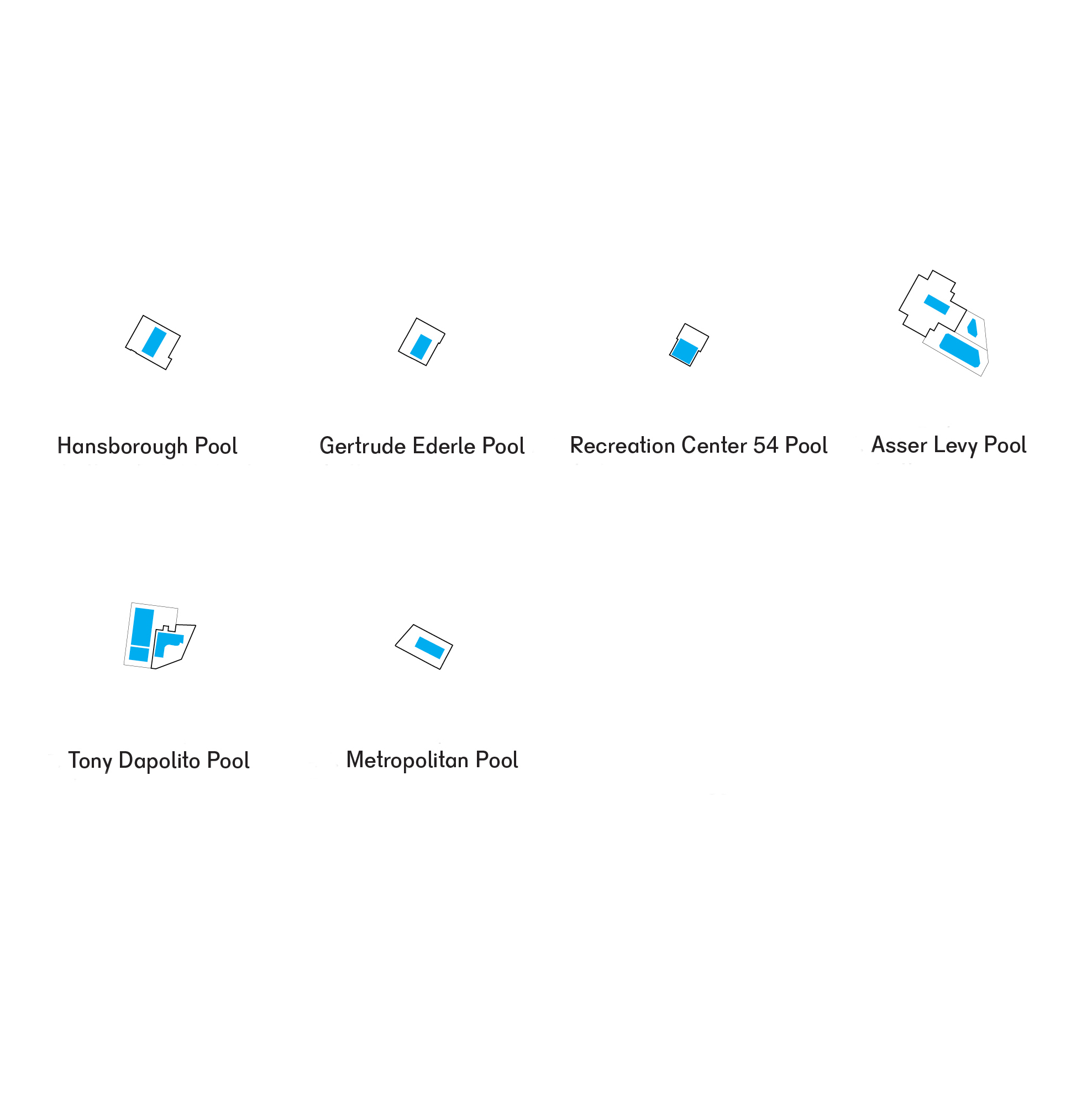

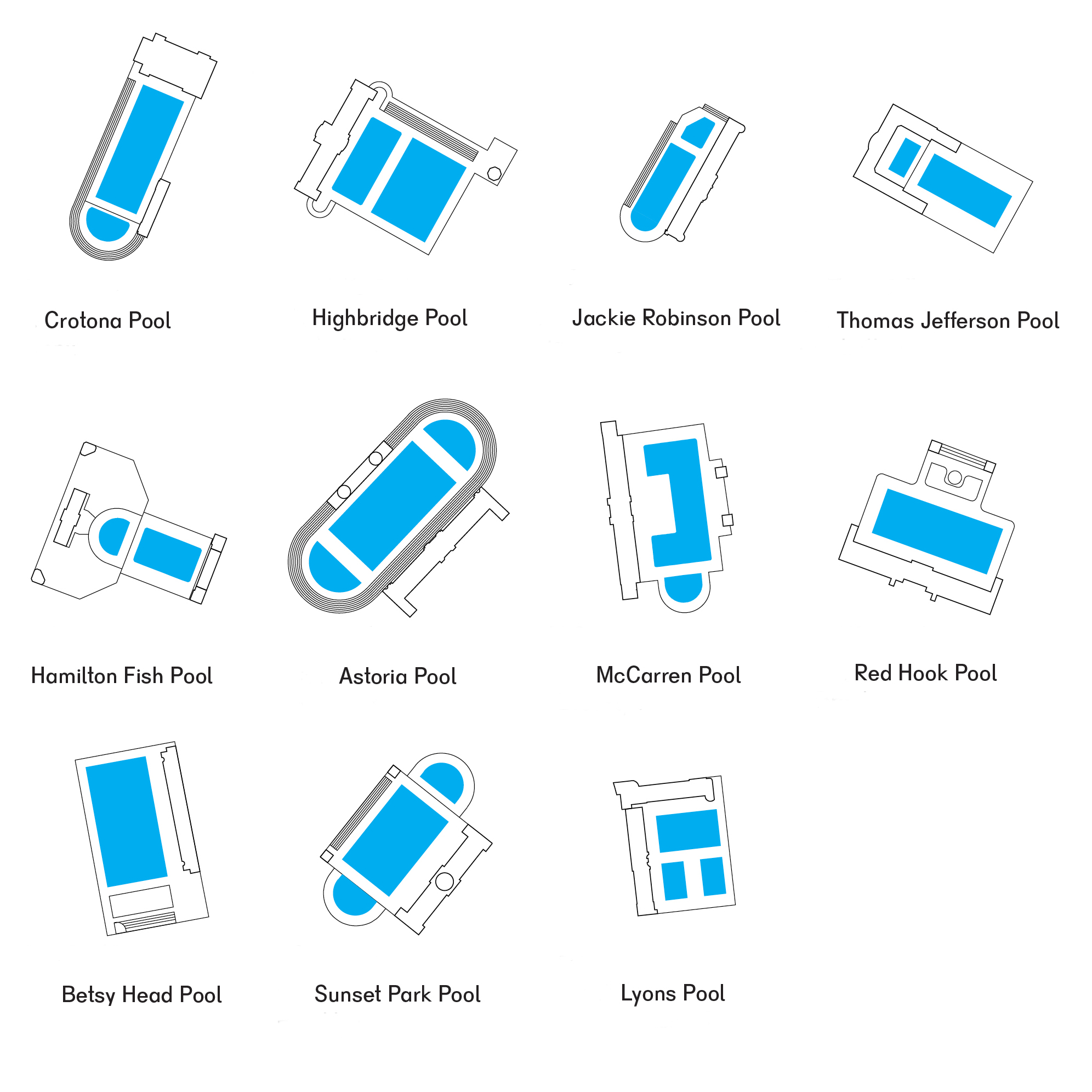

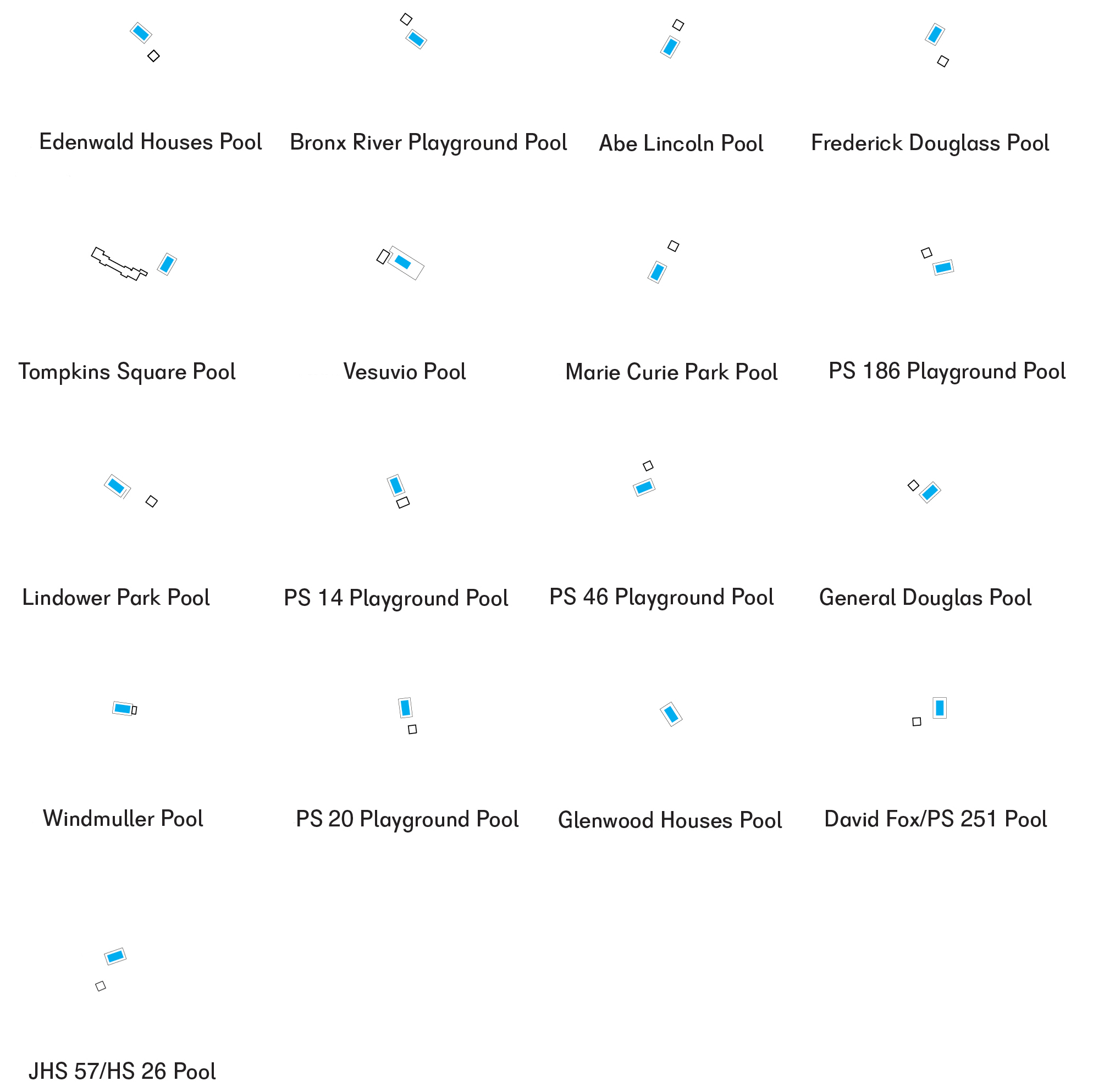

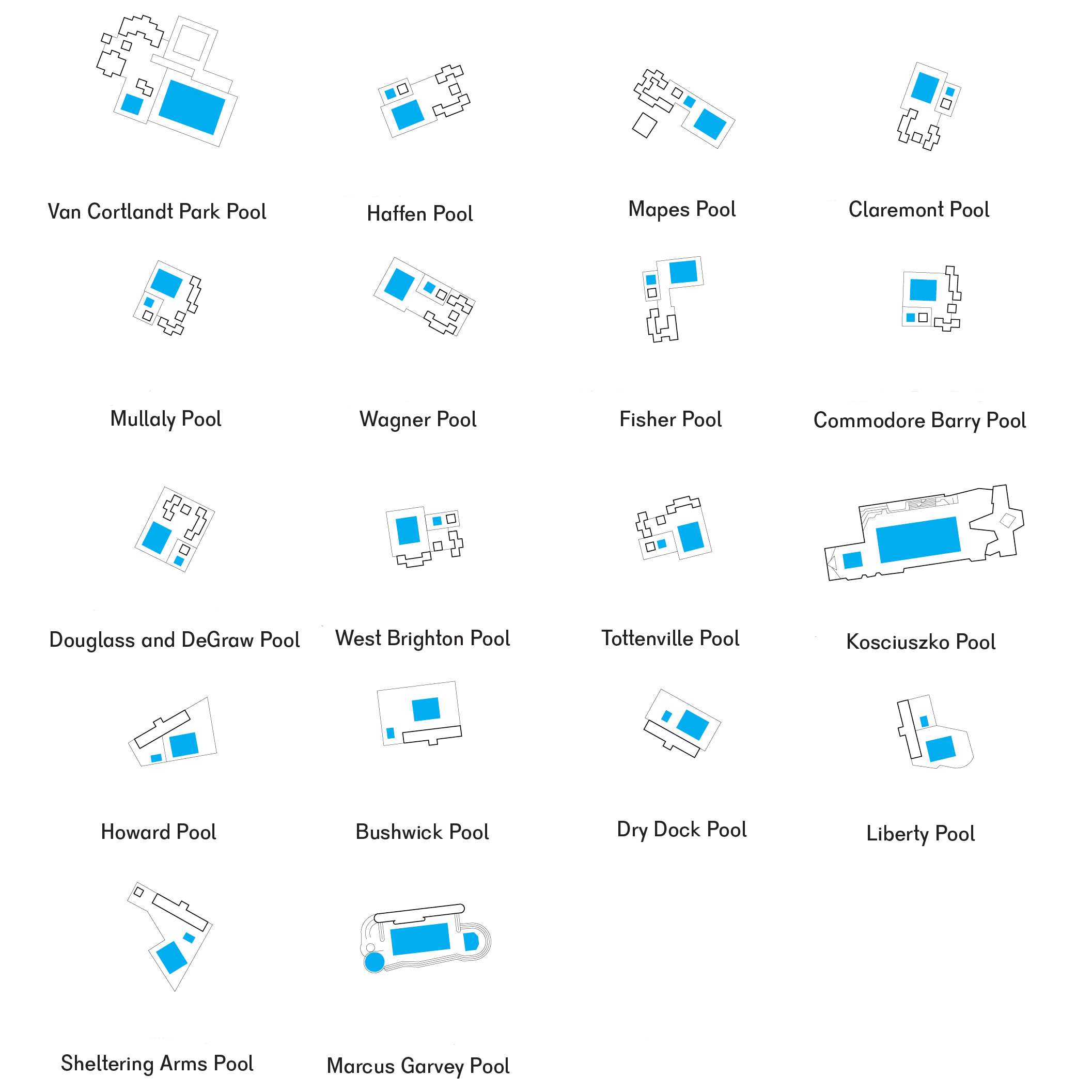

The exhibition includes a Water Map and Pool Catalogue of all sixty-five public pools in New York City. Through detailed drawings and photographs, it highlights five distinct pool types: former bathhouses, WPA-era pools, mini pools, vest-pocket pools, and an atypical example. Each type is paired with a speculative design or programmatic proposal that amplifies the potential of this existing civic infrastructure and promotes bathing culture.

Public Baths

Metropolitan Pool, Brooklyn, 1922, by Henry Bacon

In 1895, the New York State legislature passed a law mandating the establishment of public baths in all cities with more than 50,000 residents. Until then, New Yorkers had relied on floating pools in the East and Hudson Rivers, as well as natural bodies of water, to maintain personal hygiene, do laundry, cool off, and swim. The first municipal bath in New York City, the Rivington Street Bath, opened in 1901. By 1915, fifteen more public bath facilities had been established in Manhattan, along with eight in Brooklyn, one in Queens, and another in the Bronx. Inspired by European models, these facilities offered public showers, tubs, laundries, and comfort stations. As private plumbing became more widespread, diminishing their role as essential infrastructure, some bathhouses adapted by incorporating gymnasiums and swimming pools, allowing them to function as recreational spaces and offering much-needed relief during the summer heat. In 1940, several public baths were renovated, but most were closed in the years following World War II. Several former bathhouses survived until today, repurposed as indoor public swimming pools and recreation centers.

![]() Public Laundry

Public Laundry

Building on the history of public baths, this speculative programmatic proposal calls for the reintroduction of public laundromats into former bathhouse buildings. Visitors could do their laundry while attending swim classes or fitness programs, highlighting importance of physical activity and necessity of tending to domestic duties. In addition to serving a practical need, these laundromats could act as social gathering spaces and hubs for clothing donation.

![]()

Asser Levy Pool, Manhattan. Photography Anna Morgowicz

Work Progress Administration (WPA) Pools

Astoria Pool, Queens, 1936, Aymar Embury II, Gilmore Clarke

In 1936, eleven large-scale public swimming complexes opened across New York City. Built with funds from the Works Progress Administration, as part of the New Deal’s sweeping investment in infrastructure. WPA-era pools, heavily supported by New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, departed from public baths’ utilitarian role, instead providing space for safe swimming, social gathering, and much-needed recreation. These large, Olympic-size complexes also accommodated other uses, from indoor recreational facilities and public performances to off-season outdoor sports, and were equipped with the latest cleaning, heating, and lighting systems. They created a new kind of public architecture, reflecting an evolving approach to recreation and gender integration in public space All WPA-era pools continuously function until today, except for McCarren Park Pool, which, after a period of abandonment and threats of demolition was renovated, and reopened for swimming in 2012. Featured Astoria Pool is the largest New York City public pool.

![]() Cooling & Warming Center and Performance Venue

Cooling & Warming Center and Performance Venue

The speculative proposal includes weatherizing and adapting all WPA pool-adjacent recreational buildings into designated cooling centers in the summer and warming centers in winter and shoulder seasons. The former diving pool area of the featured Astoria Pool can become a year-round performance venue, capitalizing on its existing auditorium shape and size to host local dance and theatre groups, film screenings, and other programs.

Mini Pools

Abe Lincoln Pool, Manhattan, 1960’s

The second pool-building era in New York City began after the election of John Lindsay as mayor in 1966. This campaign was a response to the scarcity of water facilities and cooling infrastructure in underserved areas of the city. Lindsay’s administration built around 60 mini pools, usually located within public plazas, parks, and playgrounds. Compared with WPA-era facilities, mini pools built in the late 1960s differed significantly in form, size, and distribution. The first mini pools were designed as aboveground, prefabricated, and portable structures of fixed size, 40’ x 20’ x 3’, that could be quickly assembled, dismantled, and moved to other parts of the city. Some took the form of “swimmobiles,” or pools mounted on trucks that would circulate through neighborhoods on hot summer days. Many mini pools still exist today, and some, like the Abe Lincoln Pool, have been renovated and converted into in-ground pools.

![]()

Sauna

The speculative design proposes installing saunas on top of mini pools during the shoulder and winter seasons. Aside from their health benefits, public saunas introduce a new and alternative way to engage with water and bathing culture. Not unlike the original mini pools, small, portable sauna structures can be placed above any mini pool, providing a new public facility and winter cover for the basin. Additionally, built-in auditorium seating can serve as a gathering space for the community, an outdoor classroom, or seating for movie screenings.

![]()

PS20 Playground Pool, Brooklyn. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

Vest Pocket Pools

Mapes Pool, Manhattan, 1970-72 by Heery & Heery Architects

In the early 1970s, the city began constructing larger “vest-pocket” pools, primarily located within parks or adjacent to public schools in densely populated neighborhoods. Vest-pocket pools feature uniformly sized intermediate swimming pools (75′ x 60′ x 3.5′) and wading pools (12′ x 12′ x 1′), accompanied by repeatable building modules. While the components of vest-pocket pools remain consistent, their arrangement varies depending on the site. The modules can be used individually as shading structures or combined to house changing rooms, toilets, maintenance facilities, and other support functions. These modules are composed of prefabricated structural elements, such as concrete columns, beams, and roofs topped by a monitor volume, and are enclosed with prefabricated wall panels and a system of louvers. In 2018, as part of the Cool Pools initiative, the NYC Department of Parks & Recreation upgraded 16 vest-pocket pools with wall art, additional seating, planters, and programming.

![]()

Inflatable Pool Cover

This speculative design proposal introduces a temporary, inflatable pool cover to extend the swimming season beyond the summer months. A heated enclosure would allow the free NYC Learn to Swim program to continue during the school year, providing more children with lifesaving skills and offering additional exercise opportunities for adults. The modular, prefabricated nature of vest-pocket pools, which originally allowed for their rapid deployment across the city, makes them well-suited to accommodate a simple, adaptable cover that could be used at any of these pool sites.

![]()

Van Cortlandt Pool, Bronx. Photography Anna Morgowicz

Atypical Pools

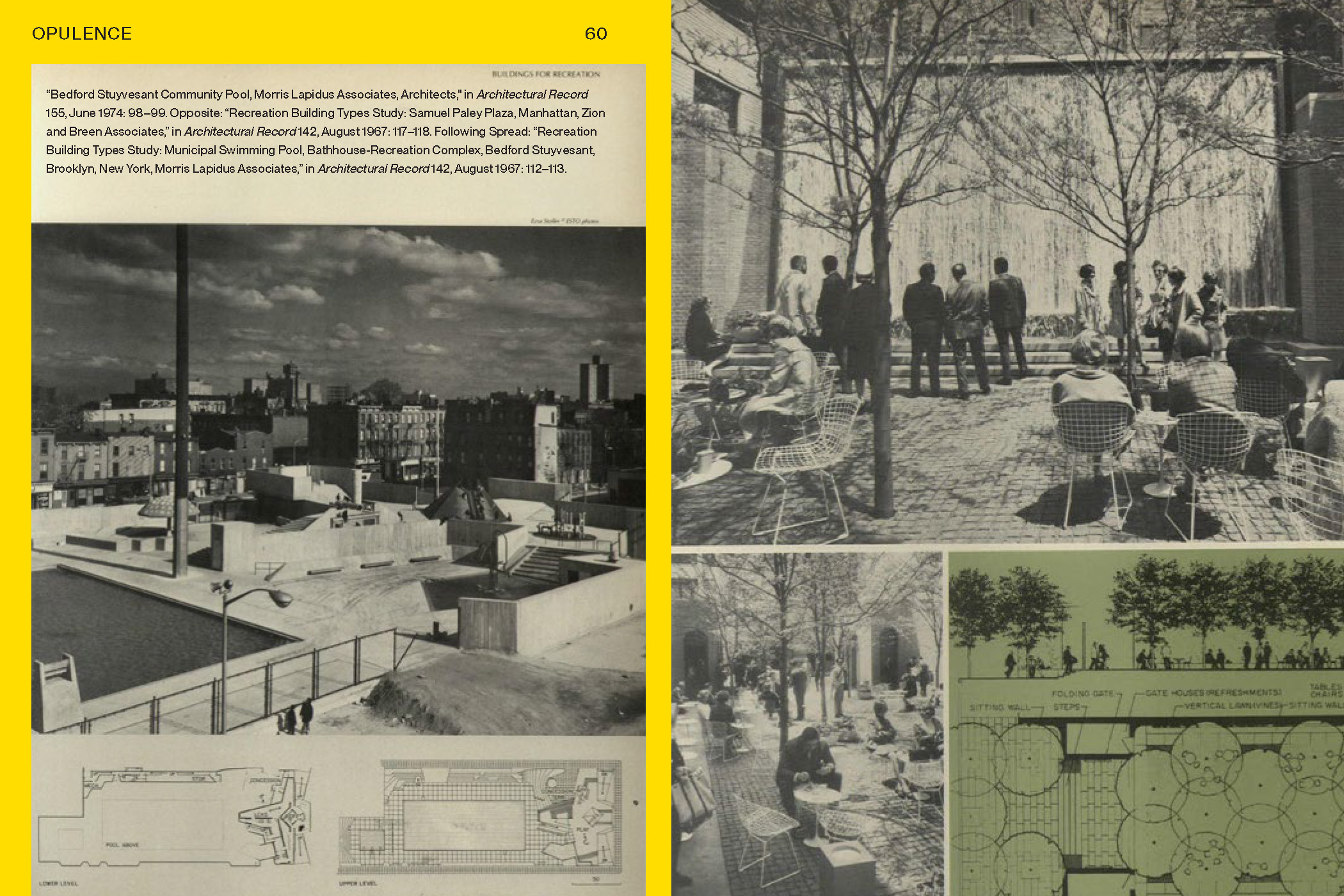

Kosciuszko Pool, Brooklyn, 1971, by Morris Lapidus

The Kosciuszko Pool represents several atypical public pools that don’t belong to other typologies. K-Pool, or People’s Pool as it is also referred to, is located in Bedford-Stuyvesant and was designed by Morris Lapidus. The architectural and social ingenuity of the Kosciuszko Pool is visible in its otherwise brutalist form. Half building, half urban landscape, the pool’s form and organization enables a wide range of concurrent activities: play, active recreation, and human interaction. A large concrete volume raised above these spaces is dedicated to the playground that appropriates concrete-encapsulated mechanical exhausts and pipes as play features. Swimming pools are surrounded by a steped topography of sun decks and bleachers that engage with the architectural language of repetitive walls outlining the pool grounds. Today, with the smaller pools and the raised playground fenced off due to accessibility and operational issues, the architecture that once embraced joy seems to be missing it.

![]()

Drawing by Only If—

Recreation Center

The design proposal includes a retractable roof over half the existing pool and the reintroduction of night lighting to extend the swimming times and seasons. The proposal also includes a new indoor aquatic center on an adjacent, vacant, and city-owned property that includes indoor water facilities, a gym, community space, offices, and a lifeguard training center. Introducing planting, cooling stations, and shading around the pool grounds reduces the heat island effect and provides cooling during more frequent and intense future heat waves. Additionally, the proposal explores the natural filtration system of the pool and provides accessibility throughout.

Design proposal for the Kosciuszko Pool was developed by Only If and featured in the inaugural Architecture Now: New York, New Publics exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 2023.

![]()

Kosciuszko Pool, Brooklyn. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

The exhibition is supported by an Independent Project Grant from The Architectural League of New York, the New York State Council on the Arts, and Citygroup. The research was made possible through access to the archives of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation and the Department of Buildings.

New York’s public pools are joyfully oversubscribed through their short, hot seasons. Like a library, but more fun, pools are social infrastructure: Long lines for entry and marginally extended hours during heatwaves point to an enduring and increasing need to splash, squeal, and cool down poolside. This summer, the brand new Gottesman Pool in Central Park — STR Architects’ replacement for the 1966 Lasker Pool and Rink — was especially popular. That pool, capacity 1,000, will reopen as an ice skating rink in November. But the city’s other 52 outdoor public pools will lie fallow until the end of next June, acres of recreational resource going unused. While pay-for-play baths and megapool developments become bigger business, and much-hyped pool innovations (benefitting from public support) have yet to deliver on their promises, the well-loved public system has barely expanded since the early 1970s. In the meantime, the city’s population has grown by about a million people and average summer temperatures have increased by 3°F. Why doesn’t the city’s swim-scape keep up with growing demand?

Perhaps the same prosaic forces plaguing other public systems are to blame — whether an eked-out extra hour of swimming, or a crushing closure due to lifeguard shortages, it might be money and motivation that matter in the end. But lack of imagination is another answer. In the speculative proposals below, Karolina Czeczek offers relatively low-intensity approaches to make the most of what we already have, stretching the footprint, and season, of the pool system a bit further with a light and clever touch. These proposals emerged out of an ongoing research project on the city’s public pools, which Czeczek shared with UO back in 2021. Revisiting these public assets, she sketches a network of communal laundries, outdoor art spaces, and even public saunas. These visions of “pool party progressivism” propose a good time as a public benefit. With growing attention to the material qualities of life in the city, and newfound interest in what city government, even with constrained resources, can do for residents, ‘tis the season for a little more municipal joie de vivre.

![]()

The main pool at Astoria Play Center can accommodate 6,200 swimmers during the open season.

All 64 public pools in New York City operate for a mere ten-week period during the summer, from the last weekend in June to the second weekend in September. This short swimming season, mostly due to a shortage of lifeguard and security staff, leaves the pools and their grounds unused for more than two thirds of the year. Aside from efforts to build more aquatic facilities, like the recently opened Gottesman Pool in Central Park and the “Plus Pool” currently under development, there is an untapped opportunity here: to both extend the swimming season and adapt the pool grounds into community spaces with rotating uses all year round.

With the integration of policy, innovative programming, and architectural design, the city’s existing pools might be reimagined as sites for social gathering, education, health . . . and year-round swimming. The following speculative interventions — ranging from programmatic extensions to architectural interventions — have been applied to five distinct typologies of New York City pools. Some, such as inflatable pool covers and sauna structures, are designed to extend the swimming season and expand the city’s bathing culture. Others focus on reimagining existing pool buildings and grounds as year-round recreational facilities, cooling centers, and performance venues. Lastly, at Brooklyn’s Kosciuszko Pool, we envision a new indoor bathing, recreation, and lifeguard training center, along with a partial permanent pool cover and smaller interventions that highlight the pool’s exceptional architecture and make it more accessible for users.

These proposals draw on research into global bathing cultures, time spent at each site, conversations with pool users, and investigation of past policy initiatives. We hope to spark a broader public conversation around the importance of free and accessible spaces for public recreation, and offer a starting point for meaningful change.

The Public Bath

![]()

Metropolitan Pool was built by the Department of Public Works as a bathhouse, before being transferred to the Department of Parks in 1935 to be operated as a recreational center.

Metropolitan Pool, Brooklyn

Built in 1922, designed by Henry Bacon

In 1895, New York State mandated the establishment of public baths in all cities with more than 50,000 residents. Until then, to maintain personal hygiene, wash laundry, cool off, and swim, New Yorkers had relied on floating pools in the East and Hudson Rivers, as well as natural bodies of water. The first municipal bath in New York City, the Rivington Street Bath, opened in 1901. By 1915, 15 more public facilities had been established in Manhattan, along with eight in Brooklyn, and one each in Queens and the Bronx. Inspired by European models, these facilities offered public showers, tubs, laundries, and “comfort stations” (public toilets). As plumbing became more widespread in private homes, public baths became less essential. Some bathhouses adapted by incorporating gymnasiums and swimming pools, allowing them to function as recreational spaces and offering much needed relief during the summer heat. In 1940, several public baths were renovated, but most were closed in the years following World War II. Several former bathhouses, including the Metropolitan Pool in Brooklyn, survive today, repurposed as indoor public swimming pools and recreation centers.

![]()

Proposal: Public Laundry

Building on the history of public baths, what if the City reintroduced public laundromats into former bathhouse buildings? Visitors could do their laundry while attending swim classes or fitness programs, no longer having to choose between exercise and domestic duties. In addition to serving a practical need, these laundromats could act as social gathering spaces and serve as clothing donation drop-off points.

The WPA Pool

![]()

Astoria Pool is the largest of the eleven New York City pools built with WPA funds, and received landmark designation in 2006.

Astoria Pool, Queens

Built in 1936, designed by John M. Hatton, Aymar Embury II, and Gilmore Clarke

In 1936, eleven large public swimming complexes opened across New York City, built with funds from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) as part of the New Deal’s sweeping investment in infrastructure, and with major support from New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. The pools departed from the utilitarian function of public baths, instead providing space for safe swimming, social gathering, and recreation. These Olympic-size complexes, equipped with the latest cleaning, heating, and lighting systems, also accommodated other uses: from indoor recreational facilities and public performances to outdoor sports in the off-season. They represented a new kind of public architecture, and an evolving approach to recreation and gender integration in public space. All the WPA-era pools have been in continuous use through the present day except for McCarren Park Pool, which closed in 1983, was threatened with demolition, and then briefly served as a performance venue in the early 2000s before it was finally renovated and reopened for swimming in 2012.

![]()

Proposal: Cooling & Warming Center and Performance Venue

What if we weatherized and adapted all WPA pool-adjacent recreational buildings into designated cooling centers in the summer and warming centers in winter and shoulder seasons? For this proposal, we looked at Astoria Pool, the largest in the city. The former diving pool area on the southern end of the pool can become a year-round performance venue, capitalizing on its existing scale, shape, and auditorium seating to host public programming like dance performances, theater groups, and film screenings.

The Mini Pool

![]()

Abraham Lincoln Pool in Harlem, adjacent to NYCHA’s Abraham Lincoln Houses, is meant for children and includes an ADA-accessible chair lift.

Abraham Lincoln Mini Pool, Manhattan

Built in the late 1960s, designer unknown

The second pool-building era in New York City began after John Lindsay became mayor in 1966. One of his main campaign platforms was to address the scarcity of recreation spaces, including water facilities and cooling infrastructure, in underserved areas of the city. Lindsay’s administration built nearly 60 mini pools, siting them in public plazas, parks, and playgrounds. Compared with WPA-era facilities, mini pools differed significantly in form, size, and distribution. The first mini pools were designed as aboveground, prefabricated, portable structures of fixed size (40 by 20 feet and 3 feet deep) that could be quickly assembled, dismantled, and moved to other parts of the city. Some took the form of “swimmobiles,” pools mounted on trucks that would circulate through neighborhoods on hot summer days. Many of the original mini pools still exist today, and some, like the Abraham Lincoln Pool, have been renovated and converted into in-ground pools.

![]()

Proposal: Seasonal Sauna

What if we installed saunas on top of mini pools during the shoulder and winter seasons? Aside from their health benefits, public saunas introduce a new and alternative way to engage with bathing culture. Like the original portable mini pools, temporary sauna structures could be placed above any mini pool, providing a new public facility and winter cover for the basin. Additionally, built-in auditorium seating would serve as a community gathering space, outdoor classroom, or seating for movie screenings.

Vest-Pocket Pools

![]()

Mapes Pool in East Tremont was upgraded in 2018 as part of the Cool Pools initiative.

Mapes Pool, Bronx

Built 1970-1972, designed by Heery & Heery Architects

In the early 1970s, also during the Lindsay administration, the City began constructing larger “vest-pocket” pools in densely populated neighborhoods, primarily located within parks or adjacent to public schools in densely populated neighborhoods. Vest-pocket pools feature uniformly sized intermediate swimming pools (75 by 60 feet and 3.5 feet deep) and wading pools (12 by 12 feet and 1 foot deep), accompanied by repeatable building modules. While all vest-pocket pools are made up of the same elements, their arrangement varies depending on the site. The modules can be used individually as shading structures or combined to house changing rooms, toilets, maintenance facilities, and other support functions. These modules are composed of prefabricated structural elements, such as concrete columns, beams, and roofs topped by concrete squares known as “monitor volumes,” which improve air circulation. They are enclosed with prefabricated wall panels and a system of louvers. In 2018, the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation’s Cool Pools initiative upgraded 16 vest-pocket pools with wall art, additional seating, planters, and programming.

![]()

Proposal: Inflatable Pool Cover

What if vest-pocket pools had temporary, inflatable pool covers to extend the swimming season beyond the summer? A heated enclosure would allow free, public Learn to Swim programs to continue during the school year, providing more children with lifesaving skills. A longer swimming season would also offer additional exercise opportunities for adults. The modular nature of vest-pocket pools, which originally allowed for their rapid deployment across the city, allows them to accommodate a simple, adaptable cover that could be used at any of the sites.

An Atypical Pool

![]()

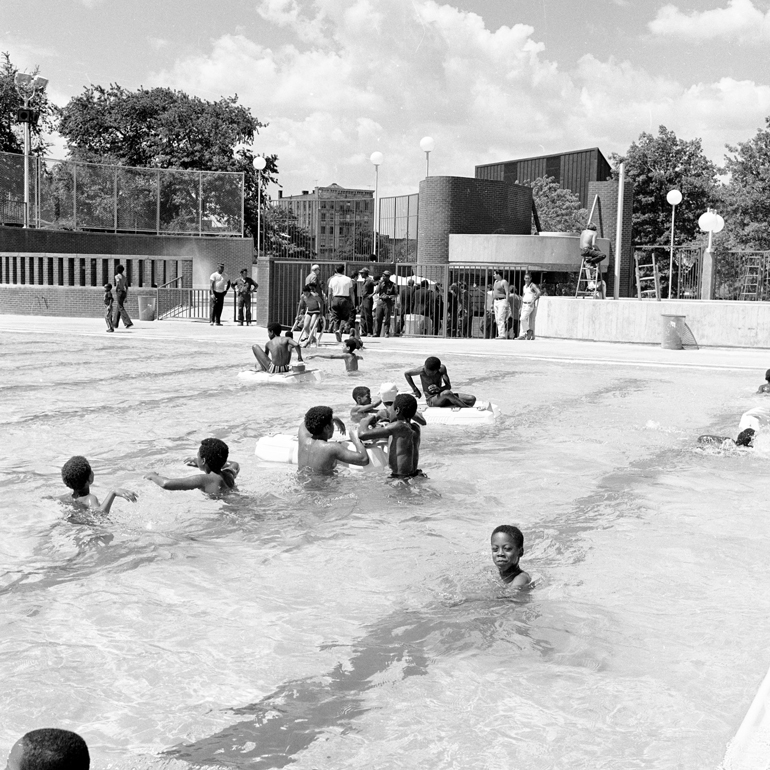

Bathers relax on stepped concrete risers at Kosciuszko Pool, which has a 3,000-person capacity.

Kosciuszko Pool, Brooklyn

Built 1971, designed by Morris Lapidus

Kosciuszko Pool represents one of several atypical public pools that don’t belong to any of the previous typologies. The architectural and social ingenuity of the Kosciuszko Pool — K-Pool, or the People’s Pool, as it is often called — is readily visible in the many ways people use its brutalist concrete forms. Half building, half urban landscape, the pool’s design enables a wide range of concurrent activities: play, exercise, and socializing. A large, raised volume dedicated to the playground incorporates mechanical exhausts and pipes as play features. Swimming pools are surrounded by stepped blue sun decks and bleachers that echo the walls ringing the pool deck. Today, the smaller pools and the raised playground remain fenced off due to accessibility and operational issues. The architecture that once embraced joy seems to be missing it.

![]()

This design proposal for the Kosciuszko Pool was developed by Only If for the exhibition Architecture Now: New York, New Publics at the Museum of Modern Art, 2023. Drawing by Only If

Proposal: Recreation Center

What if a retractable roof over half the existing pool, in addition to night lighting, could extend daily swimming hours and the pool season? Additionally, the proposal explores the natural filtration system of the pool and adds accessibility throughout. On an adjacent, vacant, and city-owned property, there could be a new indoor aquatic center with water facilities, a gym, community space, offices, and a lifeguard training center. New trees, cooling stations, and shading around the pool grounds would reduce the heat island effect and provide cooling during heat waves, which are expected to be more frequent and intense in the future.

All photographs copyright Anna Morgowicz.

All drawings copyright Karolina Czeczek unless otherwise noted.

"Landscape of Leisure”

This article is featured in the landscape architecture journal PLOT - Vol. 11 OPULENCE

"Withdrawn Waters”

This article was first published on August 11, 2021 at Urban Omnibus and in the June & July 2021 Issue of NYRA

As summer moves all too swiftly into fall, we would like to offer a humble public service announcement: Go visit one of New York City’s public pools, before it’s too late! September 12 will mark the end of a fleeting outdoor swim season, and the city’s panoply of public facilities are not to be taken for granted. But for many New Yorkers, the weather poses no such limits (in theory, at least). Tucked away in towers or behind fences, private pools are surprisingly ubiquitous throughout the five boroughs, if somewhat shrouded in mystery — and many of their owners likely want to keep it that way. At the same time, these “amenities” are a crucial selling point for single family houses, luxury high rises, hotels, and private clubs. Spurred by architect Karolina Czeczek’s recent explorations of the infrastructural and social undercurrents of the city’s shared swim spots, our friends at the New York Review of Architecture posed the question: Why does New York no longer build public pools? Nicolas Kemper and A.L. Hu expand on this inquiry below, tracing the increasing prevalence of city pools as private property. Behind this shift lie changing attitudes toward sharing in public life and public goods, in a metropolis of both legendary luxuries and staggering inequities.

From 1900 to 1972, New York City built dozens of public pools. Since 1972, the city has completed just five. What happened? One of the city’s last new, outdoor public pools, the Floating Pool Lady, was completed — or rather docked — at Brooklyn Bridge Park in 2007. Built on a barge, in 2008, the pool moved up to Barretto Point Park in the Bronx, where it remains to this day. For Jonathan Kirschenfeld, the Floating Pool Lady’s architect, “the pool was only part of what we were creating. What we really were creating was a public space. If you look at the actual pool, it only takes up a third of the barge. I think that was an indication of our priorities: to create a gathering place, a mixer.”

![]()

The Floating Pool Lady docked at Barretto Point Park, 2021. Photo by Ann Buttenweiser

That commitment to pools as a place for civic mixing used to be held by communities across the country. As Heather McGhee describes in her book, The Sum of Us, in the early twentieth century, public pools were the in thing. Towns saw pools not merely as an excellent way for people to cool down, but as focal points for civic pride — and even foundries for civil society. McGhee quotes a county recreation director in Pennsylvania: “Let’s build bigger, better and finer pools. That’s real democracy. Take away the sham and hypocrisy of clothes, don a swimsuit, and we’re all the same.”

McGhee argues that this enthusiasm came to an end when the term “public” was expanded to include everyone. Across the country, whether by law or by custom, public pools had been racially segregated. As McGhee explains, children excluded from public facilities were forced to escape the summer heat by swimming in dangerous rivers. While public pools were only officially desegregated by Title III of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, repeated drownings had already propelled a series of legal cases throughout the 1950s which led certain communities to desegregate facilities. Yet many of these communities almost immediately began to close or sell their public pools rather than follow through on integration. At the Fairground Park Pool in St. Louis, one of the largest pools in the world, violent rioting accompanied the first day of desegregated swimming on June 21, 1949. Plummeting attendance led to its closure six years later. This scorched earth approach won legal approval when, in the 1971 civil rights case Palmer v. Thompson, the Supreme Court ruled that the closure of pools in Jackson, Mississippi had harmed everyone equally. Justice Hugo Black wrote, “There was no evidence of state action affecting Negroes differently from white.” As communities closed their public pools, there was a rush to build new private pools in backyards and clubs across the nation.

![]()

Four young Black men, along with two white companions, swim in Pullen Park Pool in Raleigh, North Carolina as other white swimmers look on poolside, August 1962. This innocuous encounter proved so controversial with the white population of Raleigh as to lead to the temporary closure of all public pools in the city. Photo by David Hoffman via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

If the same trend held true for New York City, it would have ceased building public pools in the 1960s, and there would have been a boom in private pool construction. At first, during the administration of Mayor John Lindsay (1966-1973), the city bucked the trend towards racially-motivated public pool closures. Not only did the Lindsay administration keep existing pools open, it actually built a fleet of dozens of “vest-pocket” and mini-pools deployed across the five boroughs. Meanwhile, however, private pool construction began to explode.

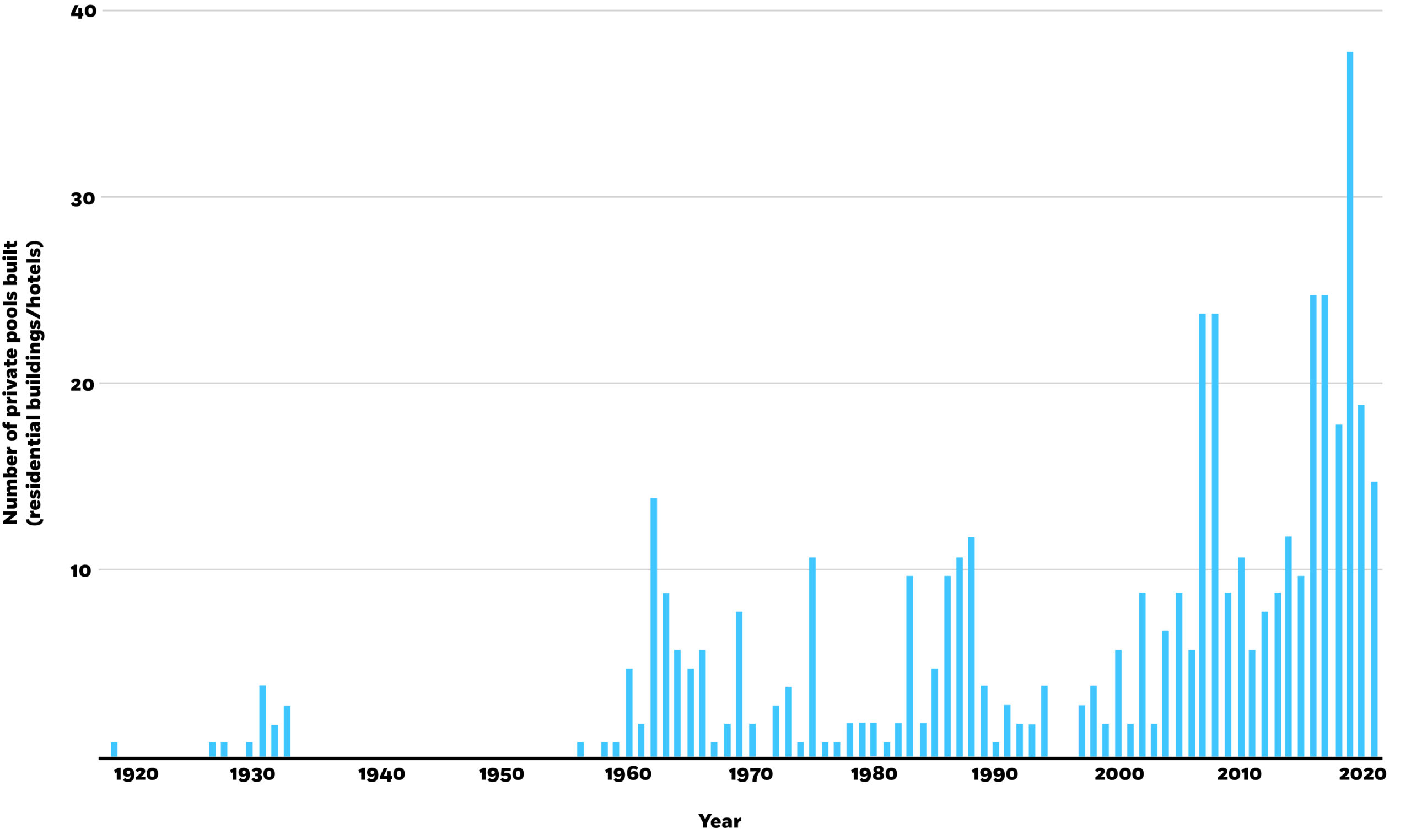

A graph showing the number of private pools built in New York City residential towers and hotels per year since 1918. By their nature, private pools are, well, private — their ownership fragmented and access guarded. There is no single authoritative list of every private pool in New York. At the same time, private pools are trumpeted amenities, often brandished by their owners and realtors in a constant campaign to sell and rent property. Many of them are therefore often much better photographed, advertised, and even known than their public counterparts. Images of private pools anchor rental listings, feed glossies, and adorn billboards. Using real estate and hotel listings, primarily from StreetEasy and Kayak — as well as the occasional phone call with a cagey property manager — we assembled a list, admittedly approximate, of nearly every residential tower and hotel with a pool, cross-indexed by construction date (or, for converted projects like the Woolworth Building, renovation date).

While a few clubs and hotels, including the Hotel St. George in Brooklyn, the New York Athletic Club, and the Downtown Athletic Club, all built spectacular pools contemporaneously with New York’s push in the 1930s to build public swimming facilities funded by the Works Progress Administration, the private sector only built about a dozen residential buildings with pools during the same decade. This changed in the 1960s: from 1960 to 1972, various developers built 63 towers with pools. Unlike Mayor Lindsay’s efforts, this boom in pool-building would be sustained and even accelerate. From 1973 to 2021, developers completed another 396 buildings with private pools.

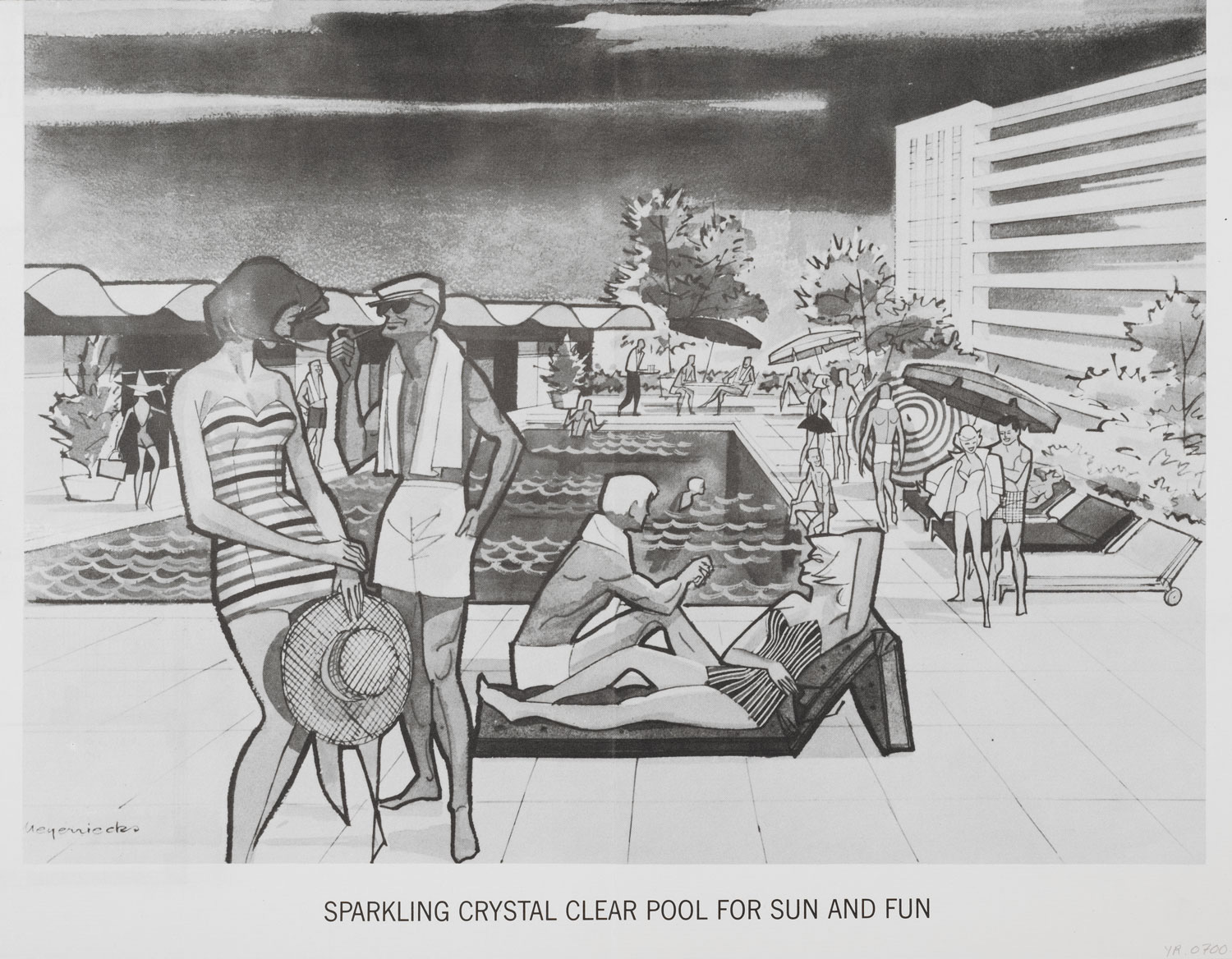

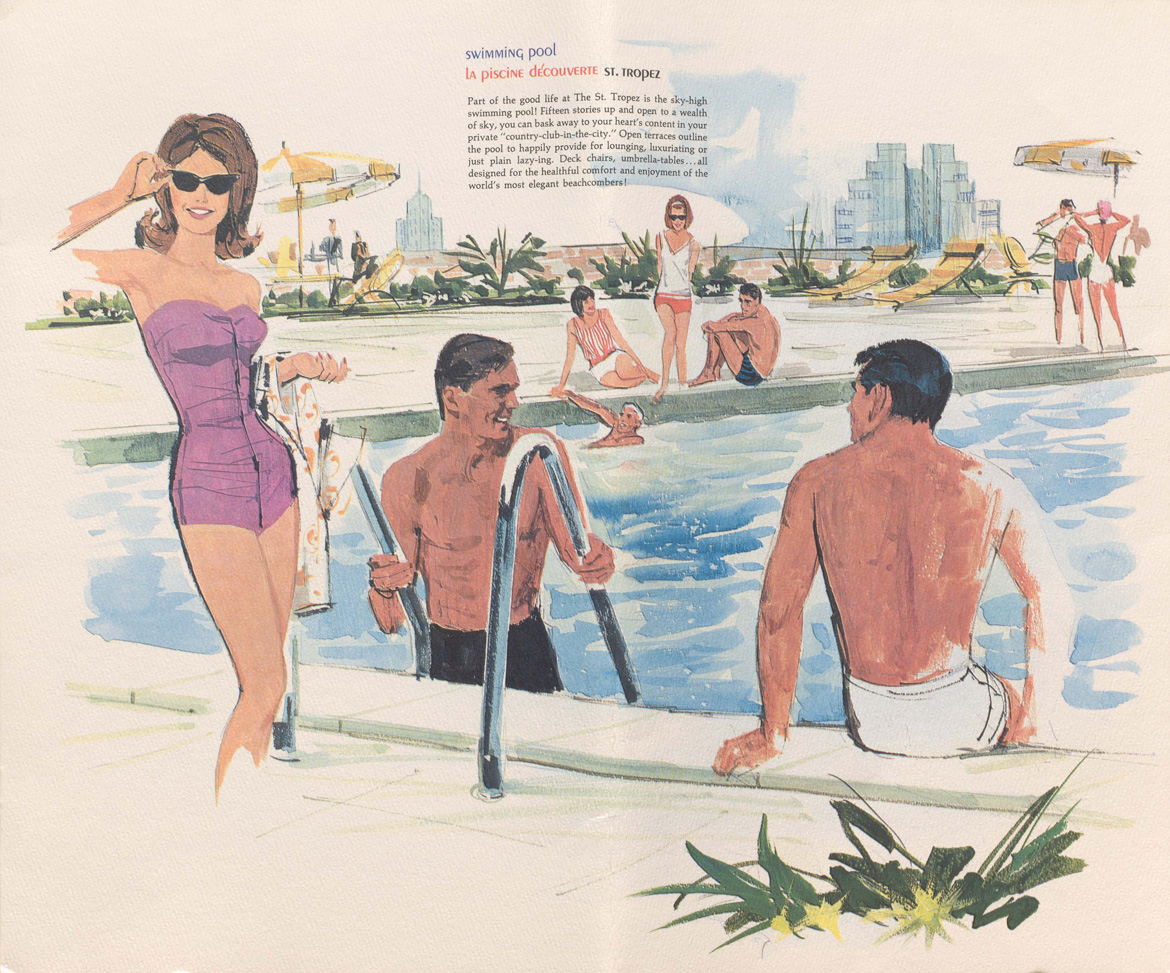

Was the boom in residential pool construction racially motivated? Possibly not. People used to go to public baths for their everyday hygiene needs; but then plumbing happened, and now most of us use private showers. We used to go to public theaters, and now we stream Netflix on our laptops — pools could be viewed as just one more front in the conquest of the public by the domestic. That said, when we looked up 1960s-era advertisements for buildings with pools in the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library’s archive of real estate brochures, race did appear to play a role. In the brochure for one of the very first private rooftop pools, Gracie Towers on 180 East End Avenue — designed by Sylvan Bien and Phillip Birnbaum (a prolific New York architect who actually claimed rooftop pools as his own “innovation”) and opened in 1960 — there is no “whites-only” sign, yet the document prominently features an idyllic rendering of a pool filled entirely with white people. In fact, in every advertising brochure we could find from this period, all emphasize the privacy of these pools (generally indoors, on a roof, or behind a fence), and feature swimmers who are predominantly, if not entirely, white (though the rendering technique sometimes creates ambiguity). In contrast with today’s real estate advertisements, which often feature pools entirely without people, advertisements from the 1960s seem to show pools as the central node of bustling (whites-only) communities.

![]()

A drawing from a brochure for Gracie Towers depicts the building’s 20’ x 40’ aluminum rooftop pool. Image from the New York Real Estate Brochure Collection, courtesy Avery Classics, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

A drawing of a pool from a brochure for The Concorde condominium tower, designed by Philip Birnbaum, in Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

A drawing from a brochure for Park City Estates, designed by Philip Birnbaum, in Forest Hills, Queens. Images from the New York Real Estate Brochure Collection, courtesy Avery Classics, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

A drawing from a brochure for St. Tropez, a condominium at 340 East 64th Street in Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Image from the New York Real Estate Brochure Collection, courtesy Avery Classics, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

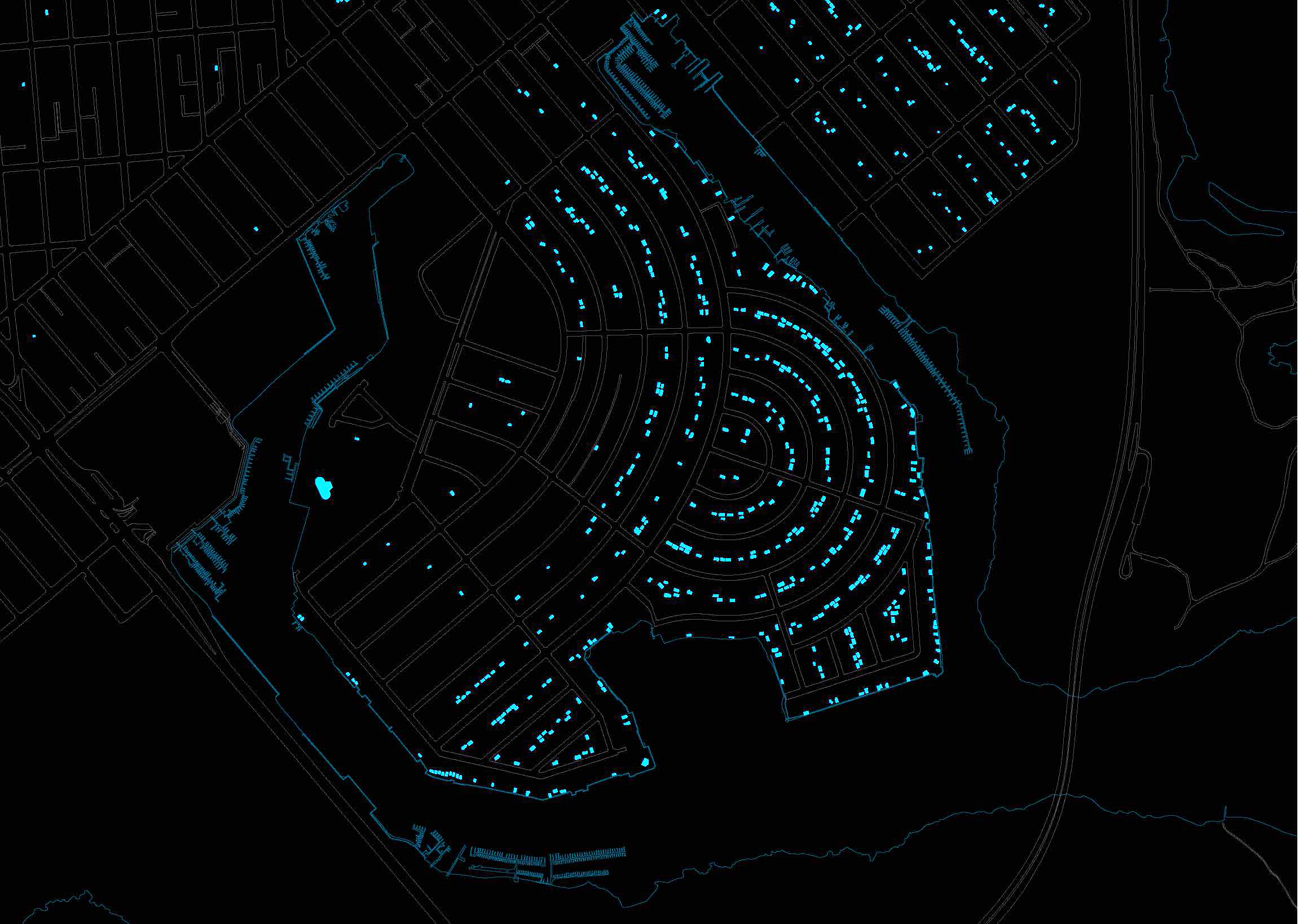

We do not have construction dates for every backyard pool in New York, but chances are very few of them predate the 1950s. According to a 1956 New York Times article, titled “They’re All Swimming in the Backyard,” until 1952 there were fewer than 15,000 private family pools in the entire country. Our dataset, assembled primarily from ArcGIS, shows that today there are 14,420 surface pools in New York city alone. These pools are clustered in neighborhoods that were predominantly built after the 1950s, such as Mill Basin in Brooklyn, largely developed from the 1950s through the 1970s, and Tottenville in Staten Island, which saw significant growth starting in the 1990s. As of the 2010 census, Mill Basin was 74 percent white, and Tottenville was 84 percent white.

Our backyard pool database was a little more challenging to gather, but with the help of graphic designer Scott Reinhard, we created a map of all 14,420 surface pools in New York City. Staten Island, with 9,994 surface pools, positively glows. By contrast, Manhattan looks empty, as most of that borough’s pools are inside towers.

A close-up of backyard surface pools in Mill Basin, Brooklyn. The large pool to the left is the Mill Basin Day Camp, a private facility advertised as the largest pool in Brooklyn.

Backyard pools in Tottenville, Staten Island. The larger pool at the far right edge of the map is the public Tottenville Pool, built in 1972.

The thesis of McGhee’s book is that structural racism is often bad for just about everyone, especially when it leads to defunding public goods (even for people with backyard pools). “The big disadvantage” of private pools, says Kirschenfeld, “is they are small, and you only meet people you know.” Yet private pools, and particularly backyard pools, are also in fact quite dangerous, simply because they do not have lifeguards keeping watch. According to the Center for Disease Control, drowning is one of the leading causes of death for children ages one through four in the United States; most of those drowning incidents happen in swimming pools, and most of those swimming pools are private. An American Public Health Association study of 678 pool-related drowning deaths in the US provides some direction on where drownings happen. This study organized drowning deaths according to pool type: public (37%), neighborhood (21%), and residential (35%). While the term “neighborhood” refers to pools affiliated with housing complexes, and the “residential” category refers clearly to backyard pools — both intrinsically private — the use of the word “public” is a little confusing, as the category includes hotel and motel pools, which account for 54% of “public” pool drownings.

Of course, there are considerable financial costs to private pools as well. There are two dominant materials used in pool construction: concrete (applied via shotcrete or gunite) and steel. Shotcrete is the overwhelming favored material for backyard and “in ground” pools, but it comes with some disadvantages for elevated construction. Whereas shotcrete is applied on site, leaving the success of a project at the mercy of the contractor holding the hose, steel is built in sections elsewhere and then welded together on site, allowing for better quality control. Whereas with shotcrete, one needs to chip away at the excess concrete to access pipes or fitting, steel allows for constant and easy access, and is much lighter. Joel Trace, a local architect who specialized in pools (and worked on hundreds of pool projects across a forty-year career, including the Floating Pool Lady), believes that most of the city’s elevated private swimming facilities are made of steel. According to Thomas Schrantz of Aqua Design International, aquatic consultants for public and private projects, any pool not “in ground” will be more expensive (he estimates a 30% markup) and steel will be even more costly (totaling about $500-$600 a square foot). For this reason, most tower pools are in fact quite small, and therefore marketers generally avoid sharing information about their size. Even when they do, only the length dimension is typically shared, as the width of such pools is often quite narrow. The website for the 432 Park Avenue, for instance, simply states that the 2015 luxury supertall has a 75-foot lap pool — photos show a single lane pool with a very narrow stripe down the middle. Tower pools also require a structural “vault” to hold them up, an expense not included in Schrantz’s estimate. And for backyard pools, as even the New York Times article from 1956 was quick to point out, the structure itself is only part of the cost, as owners will also often purchase or install pool equipment, furniture, decks, fencing, and sometimes even a cafeteria or bar.

The lap pool at 432 Park Avenue.

While New York allowed a few to fall into disrepair and close, to its credit, the City never shut down its public pools out of spite or prejudice (McCarren Park Pool was the temporary exception), and the government has stepped up its investments in public pools in recent years. The City spent $50 million to reopen McCarren Park Pool, renovated by Rogers Marvel Architects, in 2012; the Cool Pools program has upgraded 16 pools since 2018; and in 2021, the City will begin a $150 million renovation of the former Lasker Rink and Pool in Central Park, led by architect Susan T. Rodriguez. Just this May, the City granted a site to a second floating pool, the + POOL, designed by Dong-Ping Wong and Oana Stanescu. Yet since the + POOL was first proposed in 2010, developers have completed another 196 towers with private swimming facilities. While not built with public money per se, private development reflects public policy, infrastructure, and zoning decisions. As we debate new investments in public pools and weigh their costs, perhaps it is time to look at our “city’s” ongoing investment in private pools, and better weigh that cost too.

The article was guest edited by A.L. Hu and Nicolas Kemper

Nicolas Kemper is a Desk Editor and Publisher for New York Review of Architecture. He has worked for Laufs Engineering and Design and Oliver Cope Architect in New York, Hans Kollhoff and Books People Places in Berlin, and Zahner in Kansas City. Nicolas has written for AA Files, Current Affairs, ThePrepared.org, and edited the newsletter pulp. He holds an M.Arch from the Yale School of Architecture, where he also taught architectural history and edited and co-founded Paprika!, the student often-weekly. He is always looking to hear from readers; please reach him on Instagram.

A.L. Hu, AIA, NOMA, EcoDistricts AP, is a queer, nonbinary transgender Taiwanese-American architect, organizer, and facilitator who lives and works in New York City. They are a 2019-2021 Enterprise Rose Architectural Fellow. A.L. writes the not-so-regular Queer Agenda newsletter, and provides brainpower and energy for Queeries, an ongoing survey and community-building project for and by LGBTQIA+ architects and designers. A.L. has written for New York Review of Architecture, The Architect’s Newspaper, and Architect Magazine.

Outdoor public pools are back at full capacity across the five boroughs, and as swimmers return, so do a host of regulations and negotiations. There are the familiar pool rules (no running), the less obvious edicts (only plain white shirts and hats allowed on the deck), and more recent additions to official decorum, such as mask mandates (though not while in the actual pool). Then there are the usual conflicting uses — say, lap swimming versus the “floatie” crowd — which may prove to be more difficult to navigate this year, as lifeguard shortages have led to the cancellation of all swim programs for the season. But historically, pools have served as a backdrop for more salient social tensions, and their design and distribution across the city reflects larger political paradigms and aspirations. In the second installment of a mini-series exploring the undercurrents shaping public pools in New York City, Karolina Czeczek — with the help of two urban historians and a former Parks Commissioner — tells the story of their proliferation over the last century, in fits and starts. From the Olympic-sized ambitions of Robert Moses, to the “tactical” interventions under Mayor John Lindsay, to the equity- and sustainability-informed agendas put forth by contemporary renovations and new proposals, public pools have borne witness to a relationship between infrastructure and culture that has proven to be as slippery as the edge of the deep end itself (remember: no running).

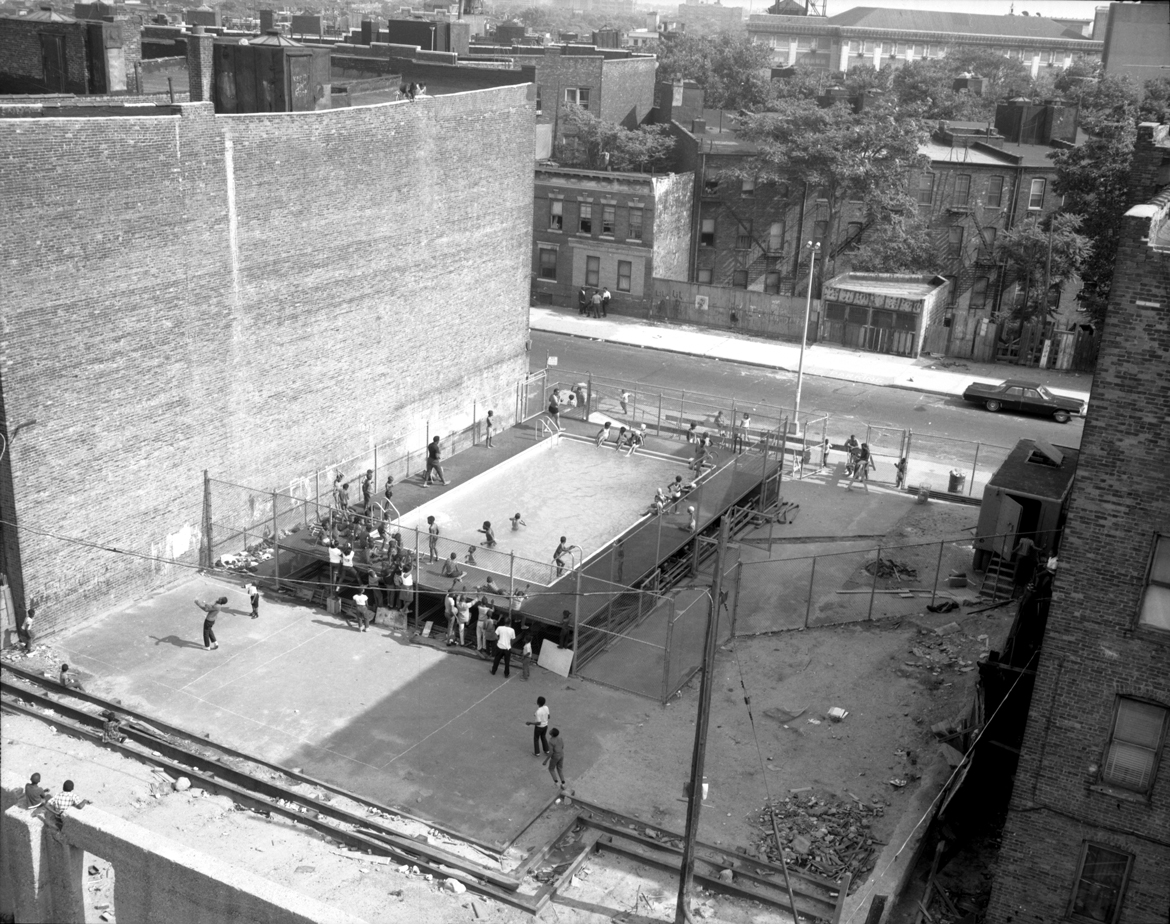

A portable pool installed in a vacant lot on Sterling Place in Brooklyn, 1967. Photo by Daniel McPartlin, courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (Parks) operates 65 public pools located throughout the five boroughs. Ranging from outdoor, Olympic-size structures to miniature and vest-pocket-sized sites and indoor facilities, these pools are invaluable public spaces — and often notable works of architecture in their own right. For more than a century, the city’s pools have doubled as both recreational facilities and infrastructure for keeping cool. This seemingly neutral network of recreational facilities has also served as a backdrop for both celebrations and disputes, reflecting larger dynamics around class, gender, and race, equitable access to public space, and public health. What can we learn from the contested history of the city’s public pools? Where does the pool fit within a broader exploration of the challenges around inequality, climate change, and resilience facing the future of cities?

New York City has seen two major periods of pool building, shaped by both the social forces and significant political figures of their times. Facilities from both eras still reflect these legacies, even as contemporary challenges and ideas present new possibilities for these now historic spaces.

![]()

![]()

An inventory of New York City's 53 outdoor and 12 indoor public pools. Two sites — Asser Levy Playground and Recreation Center, and Tony Diapolito Recreation Center — feature both an outdoor and indoor pool. Image by Karolina Czeczek/Only If Architecture

![]()

Pools in former bathhouses (1888-1936)

![]() Works Progress Administration pools (1936)

Works Progress Administration pools (1936)

![]()

Mini-pools (1968-1969)

![]() Vest-pocket (and three larger) pools (1970s)

Vest-pocket (and three larger) pools (1970s)

On July 2, 1936, thousands of New Yorkers attended the opening of Astoria Pool, with appearances from Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. The pool, designed by John M. Hatton, was the largest of eleven public swimming facilities opened across New York City that summer. Built with funds from the Works Progress Administration, as part of the New Deal’s sweeping investment in infrastructure, the pools reshaped the urban landscape. Since 1870, New Yorkers had relied on floating pools in the East and Hudson Rivers, public bathhouses, and natural bodies of water to maintain personal hygiene, do laundry, cool off, and swim. But the practical, everyday functions of public bathing facilities began to fade as private bathrooms became increasingly common in private residences. Moses’s pool-building ambitions departed from these earlier facilities’ utilitarian role, instead providing space primarily for safe swimming, social gathering, and much needed recreation. These large, Olympic-size complexes also accommodated other uses, from indoor sports to performances, and were equipped with the latest cleaning, heating, and lighting systems. They created a new kind of public architecture, reflecting progressive policies and an evolving approach to recreation and gender integration in public space.

![]()

Astoria Pool in 1936. Photo courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

This pool building spree also democratized access to public swimming, to a degree. Pools became “social melting pots” and places to be seen. However, while modern pool facilities allowed for mixing of different classes and genders, they also amplified racial prejudice in society. Robert Moses followed a “separate but equal” approach to siting pools, distributing facilities across different, racially segregated neighborhoods. Marta Gutman — a historian, architect, and faculty member at the CUNY Graduate Center and Spitzer School of Architecture at the City College of New York — provides a nuanced analysis of the complex policies and motivations behind this era of pool expansion:

The decision to build the pools was made very early in the formation of the Parks Department. Fiorello La Guardia was elected in an off-year election, and Robert Moses was installed as Parks Commissioner almost immediately. By January 1934, a city-wide Parks Department was formed, with a new ambition of thinking of the city as one thing, not as five separate boroughs. Sites for pools were chosen based on where there were already small parks that had been built as part of a Progressive Era reform project. These parks were basically early results of slum clearance, in which tenements and warehouses and factories, located particularly along the waterfront, were cleared to make places like Jefferson Park, Hamilton Fish Park, Seward Park, DeWitt Clinton, and McCarren Park. The land was available, and the addition of the pools augmented and modernized parks that needed attention.

Moses had a strong interest in making the city’s water cleaner, and he built sewage plants to make that happen. These were contemporary, modern water facilities that were installed across the city, even in working-class neighborhoods. There was never a thought that water in the city’s rivers would get clean enough for people to swim in it. That wasn't Moses’s goal either. His goal was to make the pools so attractive and so compelling that people would prefer to use them for swimming.

![]() Opening of the Sunset Park Pool, 1936. Photo courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

Opening of the Sunset Park Pool, 1936. Photo courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

In the context of New Deal politics, what happened in New York was atypical, because facilities of the same quality were built in every neighborhood. The Colonial Park pool (in Harlem) was built to exactly the same quality and standard of improvement as Jefferson Park Pool (in predominantly Italian-American East Harlem). I don't know of any other city in the United States where the facilities that were built in Black neighborhoods, if there were any built at all, were of the same quality as the facilities built in white neighborhoods. We can't dismiss that. That's a point of difference.

I think Moses could have said, “I stand for racial integration, and I'm going to do everything I can to implement policies that make it the state of policy of the Parks Department.” He didn't do that, and in my article “Race, Place, and Play,” I cite the law that he uses as his justification. He argued, that, “I can state it, but if the will of the people isn't such that they want racial integration, then I can't do anything about that.” That was his position on it. Moses believed that forcing integration on unwilling people is a really difficult proposition. We still haven't figured out how to answer that question. It requires a lot of compromise and a lot of bending and a lot of political ambition on the part of the American people that the American people have, so far, not shown to be too willing to express.

Could you have located the pools, so they sat at the intersection of neighborhoods, as opposed to deeply within them? Yes, you could have done that, and therefore, by virtue of location, pools would have worked as magnets to bring different groups of people together. That would have required buying property, clearing land, engaging in a clearance proposition that would have delayed the project. The decisions about pool siting, based on decisions about public parks that were made 30 or 40 years before the pools were even built, ended up cementing and ingraining existing social constructions of space in neighborhoods rather than reconfiguring them.

![]() Betsy Head Pool, circa 1946. Photo courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

Betsy Head Pool, circa 1946. Photo courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

For me, the politics of location are a huge question. We know that there were ways in which children and young people were challenging restrictive boundaries that their parents placed on them, and that they were trying to forge new social groupings and not be caught up in the identities that were being imposed on them by family, by their parents. We also know that there was conflict between kids of different races. But one way to think about how to create politics of tolerance in a broader community is to consider ways in which recreation can be organized to create connections, rather than enforce separations.

Looking through the lens of gender also exposes a hugely empowering agenda that was happening at the pools. In many immigrant families, gender norms constrained young girls and kept them tied to domestic duties. To have the pool just a few blocks away, to be able to go jump in, and get out of a house, was very important. It was also a way for young women to learn how to navigate a new self and to navigate public space and to take control of their life and free themselves of the patriarchy that was being imprinted upon them daily at home. I think one of the reasons that New Yorkers, in general, become so obsessed about race and pools, is precisely because that’s where young women were taking charge of their own lives and navigating their romantic and sexual relationships without their parents watching over their shoulders. We can consider the pool as a site of feminist awakening.

The Moses pools endure because they involved huge capital investments that lasted. Smaller and mobile pools are easy to lose track of; they require a different infrastructure. What I would see as a critical insight is that both kinds of infrastructure, whether small or large, in-ground or mobile, above ground or not, need to be maintained. We've given a lot of attention in our thinking about infrastructure to the initial investment; we give very little attention to thinking about the maintenance and operations that are critical to sustaining them.

![]()

![]() Sunset Park Pool, 2019. Designed by Aymar Embury II, Sunset Park Pool underwent an extensive restoration in 1984. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

Sunset Park Pool, 2019. Designed by Aymar Embury II, Sunset Park Pool underwent an extensive restoration in 1984. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

![]()

![]()

Astoria Pool, 2019. Designed by John M. Hatton, Astoria Pool hosted the Olympic Trials for the US Swim and Diving Teams in 1936 and 1964. The pool was designated a New York City landmark in 2006 and renovated in 2019. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

![]()

![]()

Highbridge Pool, 2019. Designed by Aymar Embury II and landscape architect Gilmore D. Clarke, the pool is located on the site of a former water reservoir. In 2007, the facility was designated an official New York City landmark. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

The second pool building era in New York City occurred after Moses’s fall from grace and the election of John Lindsay as mayor in 1966. Compared with WPA-era facilities, public pools built in the late 1960s and 1970s differed significantly in form, size, and distribution. Lindsay’s administration built more than 90 swimming pools throughout the city, along with new public plazas and playgrounds. The first of these pools were portable structures that could be dismantled and moved to other parts of the city; they also took the form of “swimmobiles,” or pools mounted to trucks that would circle around neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx. This initial campaign was a response to a scarcity of water facilities and cooling infrastructure in underserved areas.

The dedication of Marcus Garvey (formerly Mount Morris) Pool, 1971. The pool and bathhouse were designed by Percy Ifill and Conrad Johnson. Photos courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

The city subsequently began to install more permanent structures. Mini-pools — with completely standardized dimensions of 20′ x 40′ x 3′ — were built on vacant lots in neighborhoods suffering from disinvestment. Although ambitious in regards to their numbers, fast deployment, and strategic reuse of existing vacant space, the mini-pools were too small for swimming and not equipped with changing rooms. Their construction was quickly phased out, and the city started to build larger, “vest-pocket” pools in the early 1970s. These units featured uniformly sized swimming and wading pools (75′ x 60′ x 3.5′), but were arranged in different ways depending on the site. Vest-pocket pools were often located next to, or within, parks in densely populated areas without access to other recreational facilities. Larger pools constructed during this time include Kosciuszko Pool in Bedford-Stuyvesant, designed by Morris Lapidus, and Marcus Garvey Park Pool in Harlem, designed by Percy C. Ifill and Conrad A. Johnson. Mariana Mogilevich — author of The Invention of Public Space: Designing for Inclusion in Lindsay’s New York, and editor in chief of Urban Omnibus — provides a more extensive assessment of Lindsay’s approach to providing more equitable access to water and public space:

As Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses was well known for a massive expansion of New York City’s public realm, meaning new pools, comfort stations, beaches, playgrounds, and parks. But when you look at where it is located, you don't necessarily find a fair distribution. And you don't find nearly as many of those kinds of amenities, considered part of the privileges of urban citizenship, in neighborhoods that are predominantly Puerto Rican or African American. So even though there was this expansion of the public realm, it was partial. The civil rights movement would force a reckoning with this by the early 1960s: Who's included in that public? There are first-class and second-class citizens — everyone doesn't get the same rights and privileges. The state of people’s streets and parks spoke directly to that. Along with policing, and education, and the abominable state of housing in neighborhoods of color, they are the building blocks of a society that is separate and unequal. These conditions were being called out by liberal reformers, radical social movements, and of course are behind the decade’s racial rebellions.

When we talk about the “hot summers” of the 60s and 70s, the pools were meant to help literally and figuratively keep the city cool. Lindsay’s administration put together these urban action task forces, which involved having people who can deploy to different neighborhoods, and when things get tense, to defuse potentially violent situations, and also funding all manner of cultural and recreational activities. The way that I would look at the pools is that so many of these interventions fall under the heading of “crisis management,” or basically “anti-riot strategy.” And indeed, New York City did not see the kind of violent confrontations and property damage we associate with the uprisings in Newark, Detroit, and so many other cities.

A portable pool in Marcus Garvey Park, 1967. Photo by Daniel McPartlin, courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

In the first years of Lindsay’s administration, there was a real focus on deployable mobile pools. Building hard infrastructure takes a lot of time and money. Saying “Hey, we're here, we hear you, the city is paying attention and providing resources; this is literally on your block and can make up for those deficiencies in different neighborhoods” was an important strategy, politically and spatially. That's why you see a pool literally thrown on the back of a truck and brought to a site for a weekend. The same strategy was applied to concerts, plays, and other programming. It was pragmatic, and performed a kind of social inclusion, but also brought material improvements. There were a lot of experiments in new and improved public spaces; there was a lot of spending on cultural and recreational programming across the city, and not just in the places (predominantly white) that had been funded before.

![]()

A swimmobile, date unknown. Photo courtesy of the NYC Parks Photo Archive

The small scale of these interventions was about getting things into neighborhoods at the scale of the block — decentralizing and redistributing and getting things to where they haven't shown up before. With the vest-pocket designation, a trend emerges: There was vest-pocket housing, there were vest-pocket parks, vest-pocket pools; you could have a vest-pocket anything. It was faster and cheaper to build and avoided the large-scale demolition and displacement associated with urban renewal projects. Today we might call it “tactical urbanism.” It was responsive, and distributed, and there were a lot of good ideas tested at the time, but a lot of it didn’t survive when the vision of an expanded, inclusive public realm was replaced by a politics of fear and austerity by the mid-1970s.

![]()

![]() Commodore Barry Pool, 2019. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

Commodore Barry Pool, 2019. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

Van Cortlandt Pool, 2019. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

It was not until 1964 that Title III of the Civil Rights Act legally desegregated public facilities, including pools, and not until 1968 that the Fair Housing Act legally banned housing discrimination in the United States. These policies exacerbated the retreat of white populations from public swimming facilities to backyard pools and private clubs. In her recent book The Sum of Us, Heather McGhee describes the extreme example of the municipal recreation department, zoo, and public pool in Montgomery, Alabama all being shut down or closed following court-enforced desegregation of the city’s recreational facilities in 1959: “The council decided to drain the pool, rather than share it with their Black neighbors. Of course, the decision meant that white families lost a public resource as well.” Urban pools and other public facilities across the country fell into disrepair. While federal policies subsidized construction of segregated suburbs, they withdrew investments from public infrastructure in US cities and their “majority minority” populations.

Lindsay’s administration was the last to build a significant number of pool facilities in New York. All the city’s WPA-era and vest-pocket park pools survive to this day, but similar dynamics as those described by McGhee led to the closure of the McCarren Park Pool in 1984. After a period of abandonment and threats of demolition, local artists brought the pool back to life through live performances, paving the way for its eventual reuse as an open-air concert venue until 2008. The pool was landmarked in 2007, renovated, and reopened for swimming in 2012. Adrian Benepe, the Parks Commissioner under Mayor Bloomberg responsible for overseeing the renovation and reopening of McCarren Park Pool, describes the process:

The first discussions about renovating the McCarren Park Pool were circulated in the late 1970s, when I was the press secretary for Mayor Koch. At the time, the McCarren Park Pool area had a very different demographic from today. It was dominated by mostly Polish and Italian immigrants, who were not open to swimming with neighbors from nearby African American and Dominican communities. So, plans to renovate the pool didn't go too far. But when I became the Parks Commissioner, the idea of renovation gained new traction. By then, the area's demographics had shifted, welcoming a significant number of "yuppies" who saw the pool as an asset rather than a threat. A few years and 50 million dollars later, the pool was open again in 2012. A redesign by Rogers Marvel Architects decreased the pool’s original size, but also expanded programming for year-round use, including an ice rink (which has since shut down).

With moderate pool attendance and more contemporary state safety requirements that define pool staffing numbers, the Olympic-size WPA-era pools are difficult facilities to maintain and operate. However, they are an indispensable public asset, both in terms of public space and public safety. After the WPA era pools were constructed, a study commissioned by the Parks Department showed a sharp decline in drownings in New York City. Led by that example, in addition to renovating the physical pool infrastructure, our administration invested in education and swimming classes through the "Swim for Life" public program for second graders. With the closure of pools, beaches, playgrounds, and spray showers in 2020 due to Covid -19, I saw people once again swimming in unprotected natural bodies of water for cooling and recreation. It brought back a concern for public safety.

McCarren Park Pool, 2019. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

The last public pool built in New York City was the Floating Pool Lady, an initiative of planner Ann L. Buttenwieser and The Neptune Foundation inspired by historical floating baths. After docking at several temporary locations along the Brooklyn riverfront, the pool — which is built into a retrofitted barge — has found a permanent, summertime home in the Bronx since 2008. In 2018, the Parks Department initiated the “Cool Pools” program, which involved the renovation of selected vest-pocket park pools that had not been significantly upgraded since the 1970s. Renovations were accompanied by the addition of shading, sitting, and planting elements — along with free poolside activities, including games, sports, arts and crafts, and fitness classes — to encourage attendance during the hot season. More recently, the City’s Economic Development Corporation has given permission to proceed, with due diligence, on the construction of +POOL, the result of a ten-year campaign supported by non-profits, private individuals, and public authorities to build a floating swimming facility on the East River. The +POOL is designed to filter river water, ensuring safe swimming conditions while accommodating a range of ages and uses with areas for Olympic-length lap swimming, sports, lounging, and children.

A rendering of +POOL. Image by Luxigon. Courtesy Friends of + POOL

The history of public pools in New York traces a reciprocal relationship between architectural invention and policymaking. In light of the recent, and hopefully receding, Covid-19 crisis, along with the growing and interconnected impacts of inequality and climate change, pools have new, critical roles to play in the urban environment. Pools can take on novel functions, whether through adjustments to their physical footprint or expanded programming. Facilities that operate only a fraction of the year could open their doors to other functions and users during off-season times, offering more permanent space for social gathering, education, and health. And with every summer seemingly getting hotter than the last, the need for expanded water infrastructure will be critical for making sure New Yorkers can continue to keep cool when it matters most. Such overdue changes require an integrated social and spatial approach to addressing both the immediate and long-term needs of the communities that public pools serve.

Comments from Marta Gutman, Mariana Mogilevich and Adrian Benepe have been adapted from interviews conducted by the author.

After a long and cautious lull, New Yorkers are dipping their toes back into a fuller spectrum of public life — and soon, they will literally be able dip their toes back into the waters of New York’s municipal swimming pools. June 26, 2021 marks the reopening of most outdoor pools — indoor facilities will remain closed until further notice — and rising temperatures signal the swift approach of swimming season. But while summer fun is certainly on the agenda, the stakes are more than recreational. With access to air conditioning and green space following the city’s geographies of inequity, largely along lines of race and class, beating the heat is, for many, more than a matter of convenience: it is a major public health issue, even a life or death matter, increasingly so in a warming world.

Like the flow of water from New York’s upstate reservoirs to your favorite swimming spot, the story of the city’s public pools follows a complex trajectory through broader social histories. In the first installment of a three-part mini-series tracing these undercurrents, Karolina Czeczek situates public pools within the larger evolution of New York’s water supply system, and affirms their role as an adaptable and critical infrastructure for health and public space.

Because it remains largely out of sight, New York City’s water supply is often thought of as a purely technical matter; the more layered, private and public roles that water infrastructure plays in the urban landscape tend to escape wider conversation. Public pools, water splashes, drinking fountains, public bathrooms, and hydrants are all critical infrastructures for health, hygiene, and public space. By looking at specific elements of the historical and contemporary water supply system, we can trace its centrality to urban growth and resiliency. How should we manage the city’s water supply, and its ability to meet New Yorkers’ demands for hydration, recreation, and heat mitigation in the future, especially in the light of the climate crisis?

New York City is known for having one of the cleanest and most reliable municipal water sources in the US. The Croton, Catskills, and Delaware watersheds, located in upstate New York, cover 1,972 square miles, and contain 19 reservoirs with a combined capacity of 550 billion gallons. By virtue of the Watershed Protection Program, run by the city’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), the water originating from these far-away reservoirs does not require extensive filtration, whether flowing to private water taps or street hydrants. DEP operates two tunnels that supply New York City with one billion gallons of water each day. After a series of delays, the decades-long construction of a third tunnel, started in 1970, is nearly complete. From these tunnels, water is then distributed across the city via a 6,800-mile network of pipes. Beyond office and residential tap water connections, water also flows to some 109,526 hydrants, 1,103 public bathrooms, 841 spray showers, 3,120 drinking fountains, and 65 active public pool complexes in New York City. DEP also operates 965 sampling stations across the city, which are monitored monthly for pollutants to ensure water quality and safety.

Map showing all elements of the historical and contemporary water system in New York City, including the Old and New Croton Aqueducts. Illustration by Only If Architecture

Urban growth and an increasing demand for clean water have driven the evolution of New York City’s complex water supply system over the past 200 years. In the 1820s, city officials decided to create a public water system to replace an unhealthy and unreliable network of collection ponds and cisterns. The Croton Reservoir, Croton Dam, and Croton Aqueduct, located in Putnam and Westchester counties, were opened on July 4th, 1842 to provide a flow of freshwater to Manhattan. The aqueduct, in particular, was an enormous engineering undertaking, started by Major David B. Douglas and continued by John B. Jervis, who led the final design stages and construction efforts. 40 years later, the burgeoning city enlarged its nearest watershed and constructed a New Croton Aqueduct to the west of its predecessor. After the full incorporation of New York City’s five boroughs, the water system was expanded yet again with the annexation of the Catskill and Delaware Reservoirs further north, and the construction of the first and second water tunnels.

Profile and ground plan of the lower part of the Croton Aqueduct, drawn by John B. Jervis in the mid 19th century. Image via New York Heritage Digital Collections

Leaving the Croton Reservoir, water coursed through a horseshoe-shaped, eight-and-a-half-foot-high by seven-and-a-half-foot-wide, brick-lined masonry tunnel. At different points along its 41-mile span, the Aqueduct was buried underground, covered by embankments, cut into the rocks, and siphoned or carried across bridges through the valleys and rivers. The primary infrastructure was supported by a network of masonry ventilators, weirs, culverts, gatehouses and keeper’s houses, which assured an uninterrupted gravity flow of the water from the source to its final destination.

![]()

High Bridge and High Service Works and Reservoir, from D.T. Valentine’s Manual of the Corporation for the City of New York, circa 1869. Water was carried over the Harlem River via the High Bridge, which also served as a pedestrian promenade. The bridge’s infrastructural function was quickly overshadowed by its popularity as a local tourist destination. Shortly after the Old Croton Aqueduct was decommissioned in 1965, the bridge walkway was closed to the public. However, the High Bridge pedestrian promenade was recently renovated and reopened in 2015. Image via the Library of Congress

![]()

A lithograph of the Murray Hill Reservoir by N. Currier, 1842. This endpoint of the Old Croton Aqueduct was considered the public “face” of the Croton System. Designed as a two-chamber, 24-million-gallon structure in an Egyptian Revival Style, the perimeter was topped by a public promenade accessible by a series of staircases from the street level. Image via the Library of Congress

It was not only flow, but also storage, distribution, treatment — and, eventually, recreational use — that formed the city’s approach to water management, resulting in the construction of several civic engineering marvels. Once it reached the city, water was stored in artificial reservoirs distributed across various neighborhoods. The Croton Reservoir in Central Park (now the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir) and Jerome Park Reservoir in the Bronx were designed as groundwater bodies with recreational paths laid out around their perimeters. The York Hill Reservoir in Central Park (now the Great Lawn), High Bridge Reservoir in Washington Heights, and Murray Hill Reservoir were architecturally distinct structures with a monumental presence.

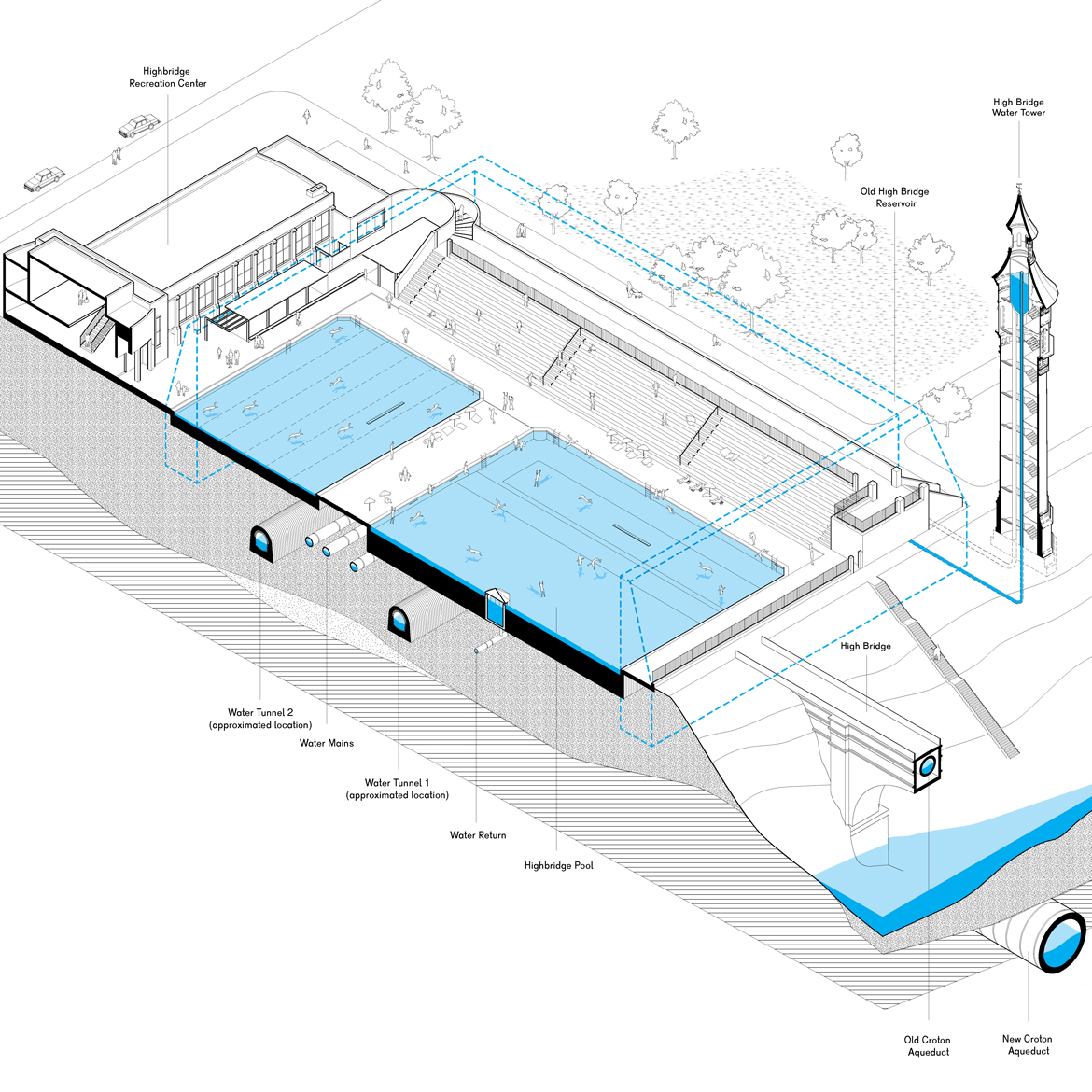

Highbridge Pool was built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) within remnants of the High Bridge Reservoir, and opened in 1936. Illustration by Only If Architecture

The city’s local reservoirs were decommissioned with the completion of the first and second water tunnels in 1917 and 1936, respectively. Some were turned into recreational areas and integrated into the surrounding parks system, while others were demolished to make way for new development. The site of the Murray Hill Reservoir, for instance, was later transformed into Bryant Park; part of the old reservoir’s foundations were used to construct the New York Public Library in 1911. The High Bridge reservoir, with its iconic water tower and bridge, was adapted into a public swimming pool in 1936. Meanwhile, the Croton System as a whole was eventually decommissioned in 1965, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992; several of its extant structures have been designated as Historical Landmarks. The Aqueduct Trail, alongside a stretch of the original tunnel, is now a State Historical Park; it continues through the Bronx as a City-managed park, fully preserved. The architectural ingenuity and scale of much of the city’s original water infrastructures, which had already served as great civic markers during their operation, were later adaptable for more obvious social and environmental purposes.

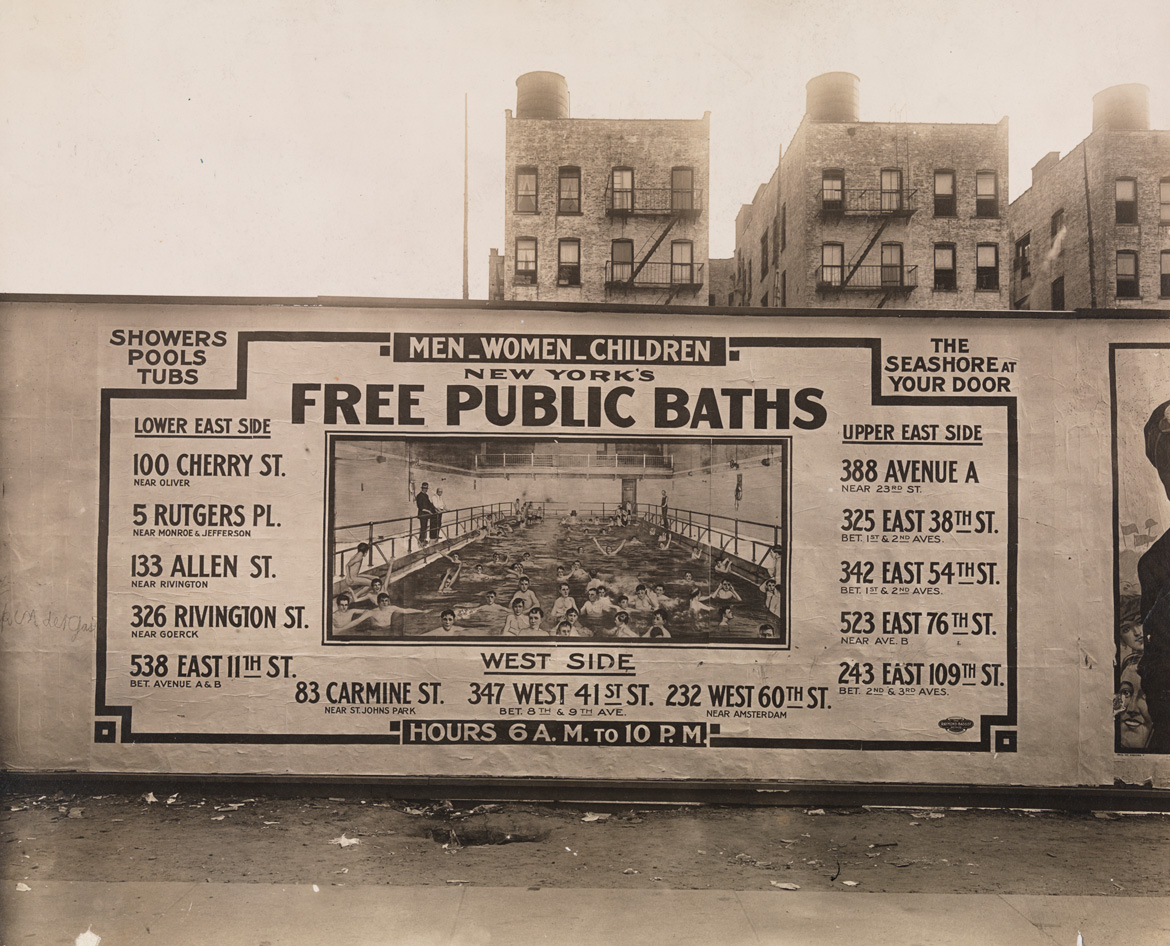

This sign advertising New York’s free bathing facilities first appeared on 23rd Street around 1935. Image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

Hansborough Pool, formerly the 134th Street Bathhouse, in Harlem, 2019. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

With the construction and expansion of the water supply system, private bathrooms became commonplace for middle and upper-class New Yorkers. However, access to fresh water was still limited for the majority of working-class people. In 1895, the New York State legislature passed a law mandating the establishment of public baths for all cities with more than 50,000 people in the state. The first municipal bath in New York City, the Rivington Street Bath, opened in 1901, and by 1915, 15 more public bath facilities were established in Manhattan, alongside eight in Brooklyn, one in Queens, and one more in the Bronx. Inspired by European examples, the baths provided public showers, tubs, laundries, and comfort stations (or restrooms). Baths sometimes doubled as recreational destinations; some were even located within the city’s parks and equipped with gymnasiums and swimming pools. As the proliferation of private plumbing diminished their function as a public utility, the baths continued to offer relief during the summer heat. In 1935, several public baths across New York were renovated by the WPA, but most were closed after World War II. Some former baths still survive to this day as indoor public swimming pools and recreational centers, such as Asser Levy Bath in Manhattan or Metropolitan Bath in Brooklyn.

Lasker Public Pool in Central Park, 2019. The pool is to be demolished in 2021 and rebuilt by the summer of 2024 with the goal of better integrating different sections of the north end of Central Park and increasing community access. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

McCarren Park Pool in Brooklyn, 2019. The pool was renovated in 2012. Photography by Anna Morgowicz

As the city’s public baths shed their original public health purposes, swimming pools connected the city’s water supply to public spaces for recreation and social interaction. Increased demand for leisure facilities in the first decades of the 20th century fueled the construction of municipal swimming pools. Eleven large-scale pools were built with WPA funds and labor and opened within weeks of one another in the summer of 1936; more facilities were constructed throughout the 1960s and ’70s. Today, New York’s Department of Parks and Recreation operates 65 active public pool complexes — 53 outdoor, twelve indoor — normally open from Memorial Day through Labor Day weekend (this schedule has shifted in the last year due to Covid-19 restrictions; only 15 of the City’s outdoor pools eventually opened in 2020). Average attendance on any given weekend day reaches 30,000 people, with the biggest pools each accommodating more than 2,000 swimmers per day. While these pools support significant numbers of swimmers, their overall capacity is too small to match the population as a whole.